Now th’ evening glow of my life

Will sink in the dark lap of the night.

What am I still searching for in this world?

Nothing – But memories bring me new life.

MY MEMORIES

Written in my 80th year of life,

With the help of my very dear wife

And my dear daughter Dorle.

Dedicated to all my descendants

Stefan Haupt–Buchenrode

Rio de Janeiro, 1949 – 1951

Translated from German to English by his granddaughter:

Marie-Louise (Haupt-Buchenrode) Thuronyi.

Proofread by Barbara Yingling.

THE TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE.

I finished translating my Grandfather’s “My Memories” on May 8th, 1998, in Paranavai, Brazil. It was Mothers’ Day and I would like to pay special homage to all the exemplary, outstanding “mothers” of the family written about in this book. I recall a sentence in my mother’s last will: “Love each other as I have loved you.” These words should unite - also in the future - all our family.

The idea of doing this translation was to keep this interesting family history alive for future generations and to carry on our aim “PRORSUM” (onward). Only a few of the younger generation will read German, so I chose English as the language most suitable for the future. Whenever I added information about an event that occurred after my Grandfather’s death I indicated it with a *[ ].

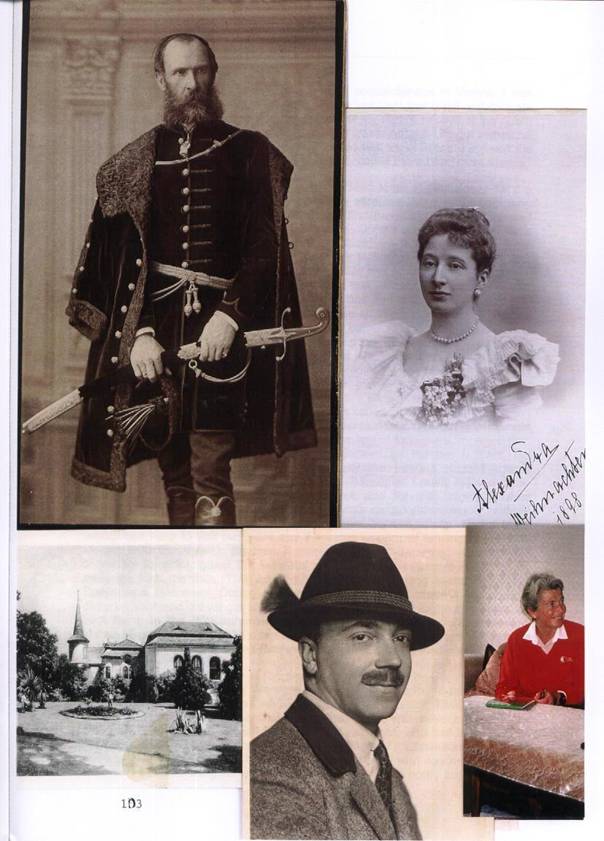

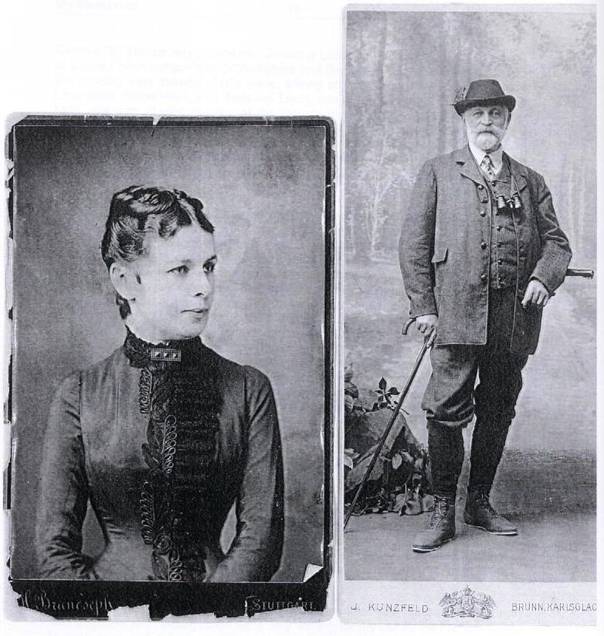

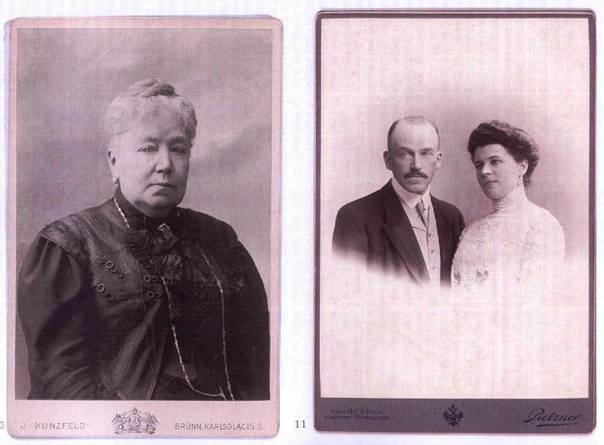

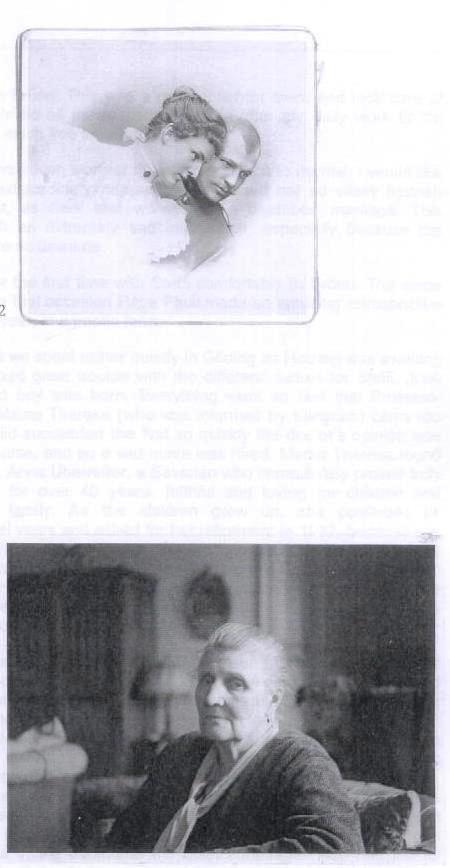

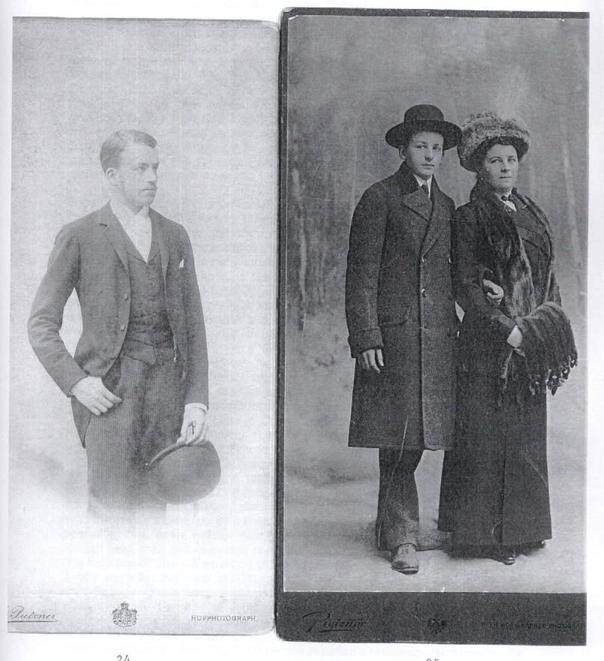

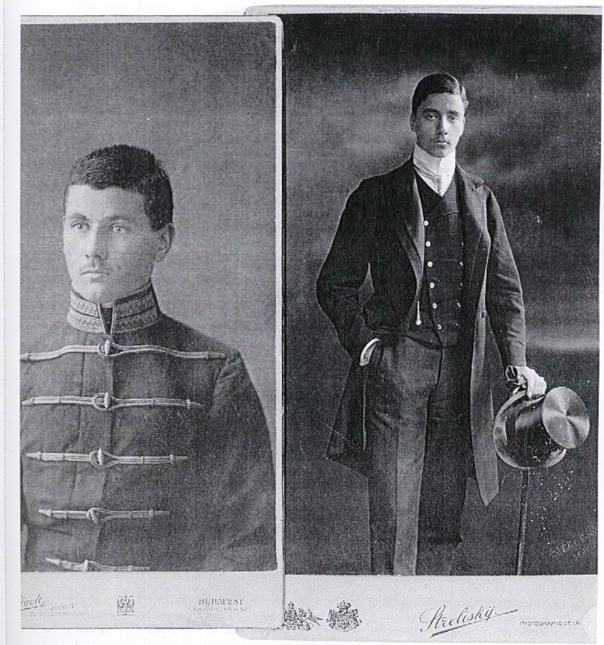

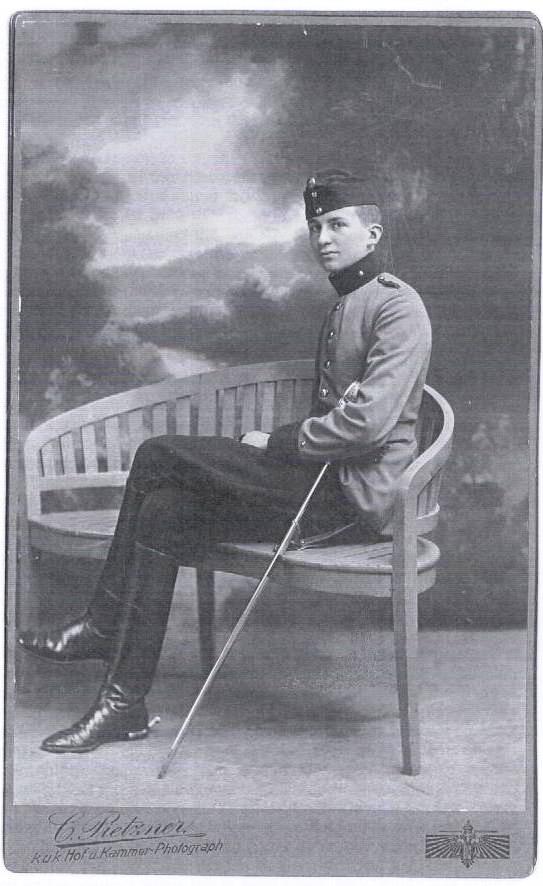

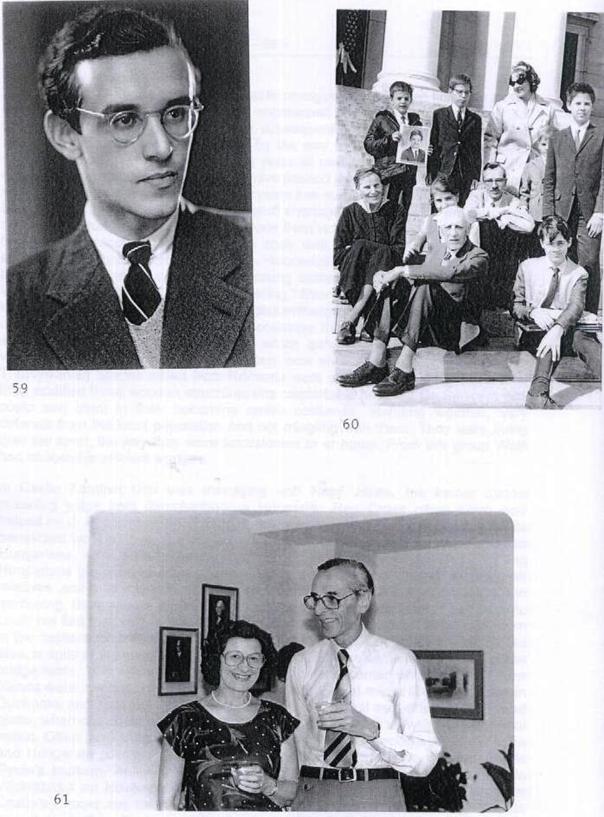

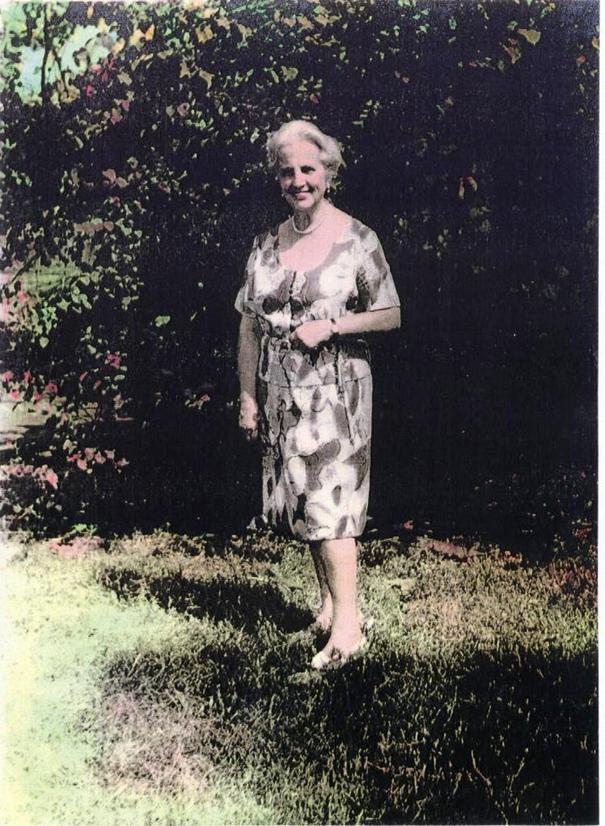

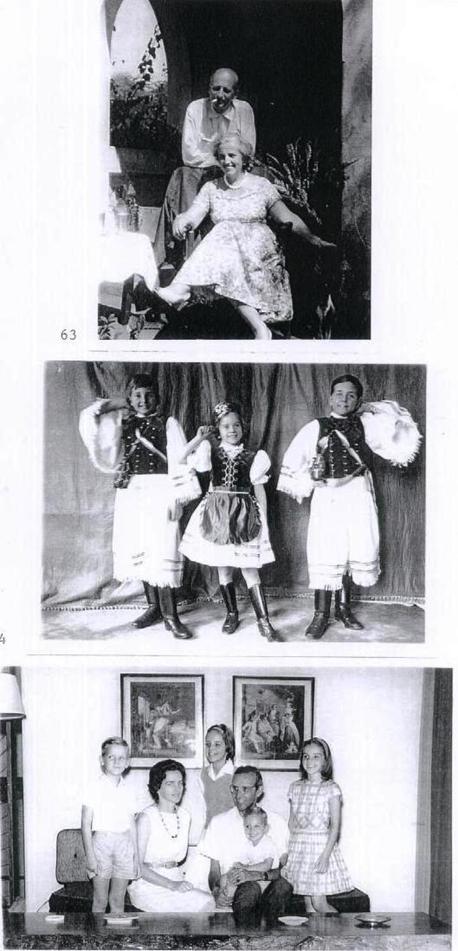

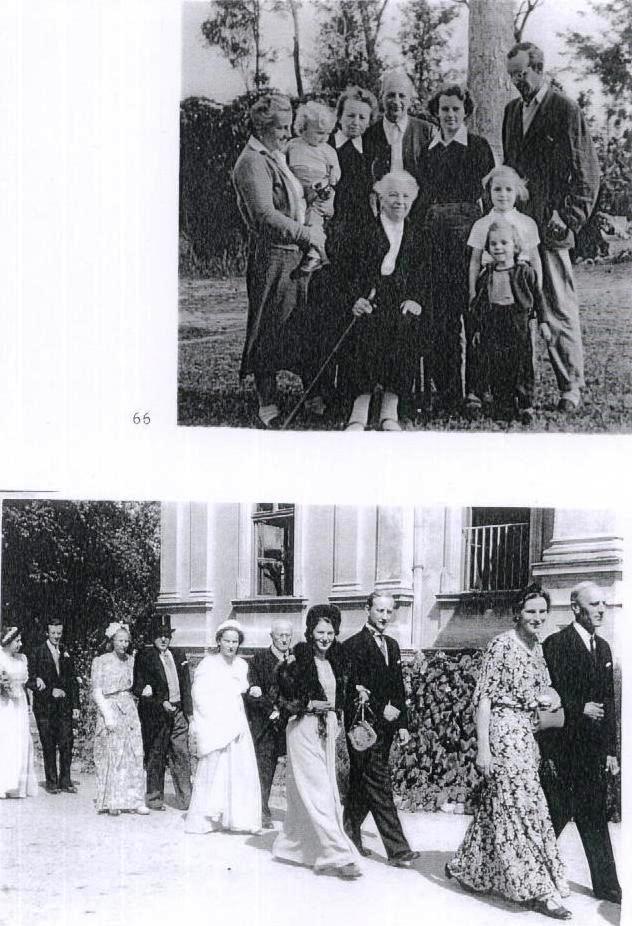

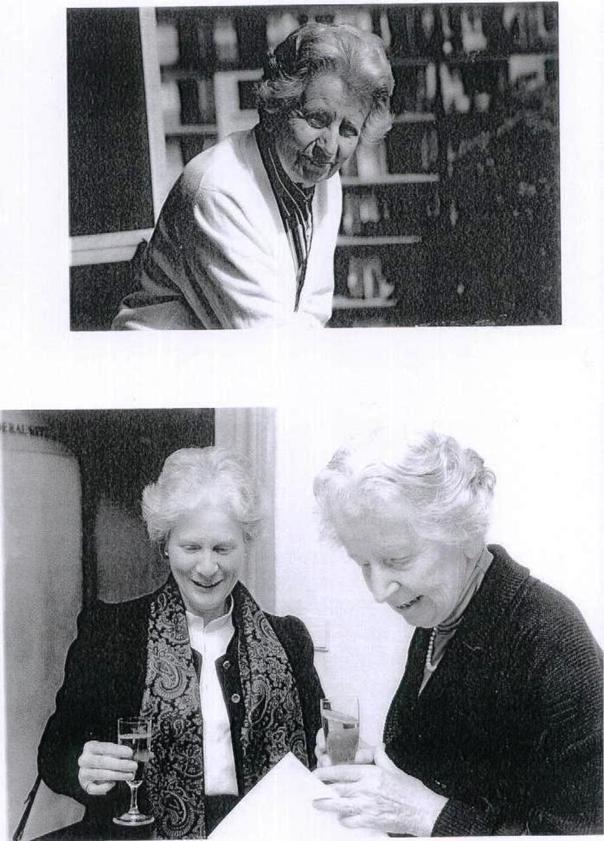

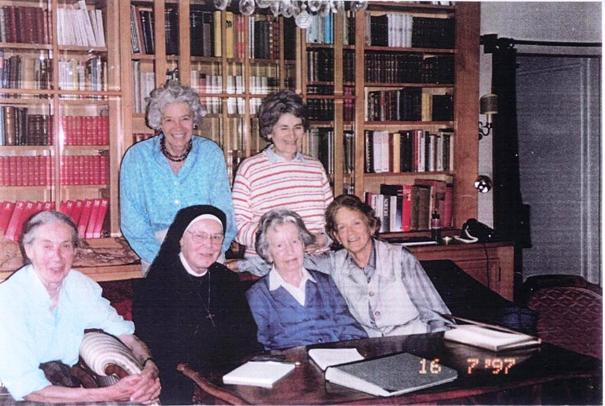

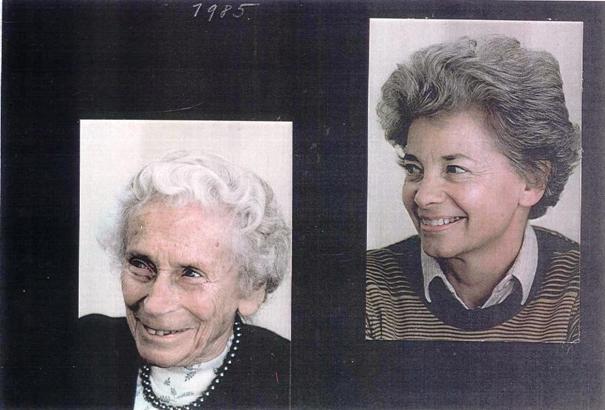

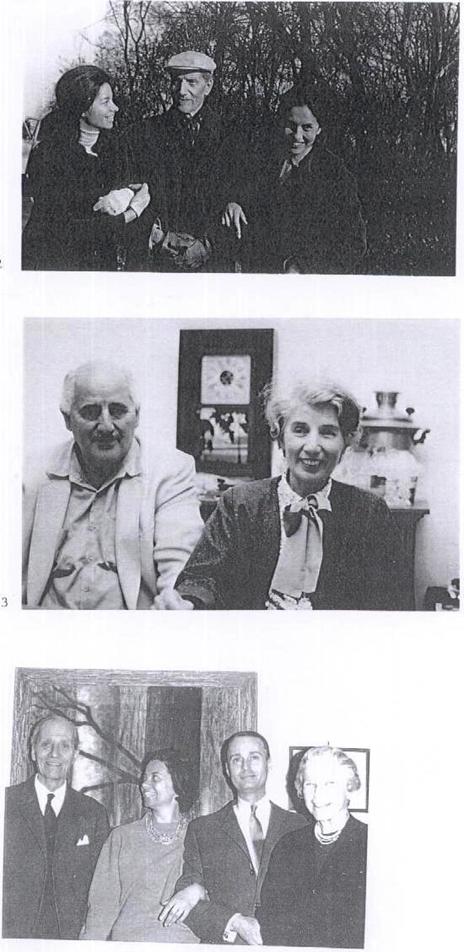

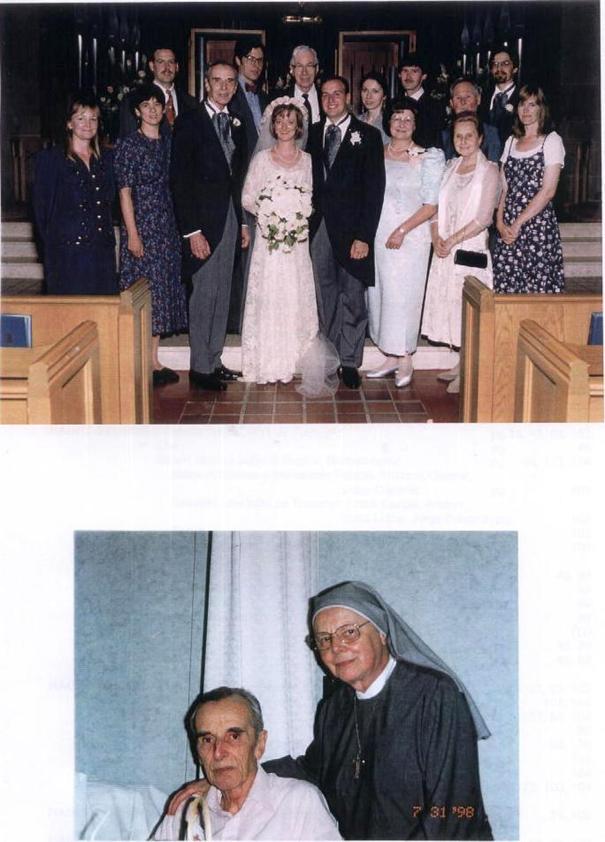

I enjoyed doing this work, living in the past and reviewing so many well-known memories of our wonderful childhood. I hope that some of my children and grandchildren and relatives will read this family history; if so, my work will not have been in vain. The original German book has no chapters, nor pictures. I made an overall selection of over 100 pictures to meet everyone’s interest, and to make it easier to understand “who is who” with Haupts and Stummers.

My gratitude goes to Barbara Yingling, who did a wonderful job with her precise proofreading. She is a niece to Jake Sheaffer, our cousin Lucia Pretis-Cagnodo’s late husband. Lucia also helped a lot, and we had fun doing some of the translation during evenings in Tucson, Arizona.

MY MEMORIES

Stefan Haupt-Buchenrode

C O N T E N T S

Mährisch – Rotmühl 1676 – 1805. 1

Brünn 1805 – 1899. 1

Zlin 1899 – 1928. 24

Switzerland 1918 - 1920. 49

Sorokujfalu 1920 – 1945. 67

Duchonka 1928 – 1944. 74

The Second World War 1939 – 1945. 83

Salzburg – Kammer 1944 – 1948. 90

Emigration – Brazil 1947 – 1948. 99

*P.s. A Register of THE "lived present of the younger Generation" 102

*APPENDIX TO REGISTER OF THE "LIVED PRESENT OF THE YOUNGER GENERATION" 105

*INDEX Of PICTURES …………………………………………………………………………………… 106

This document has:

Ø 112 pages

Ø 103 pictures

Ø 802 paragraphs

Ø 5,542 lines

Ø 66,313 words

Ø 321,285 characters

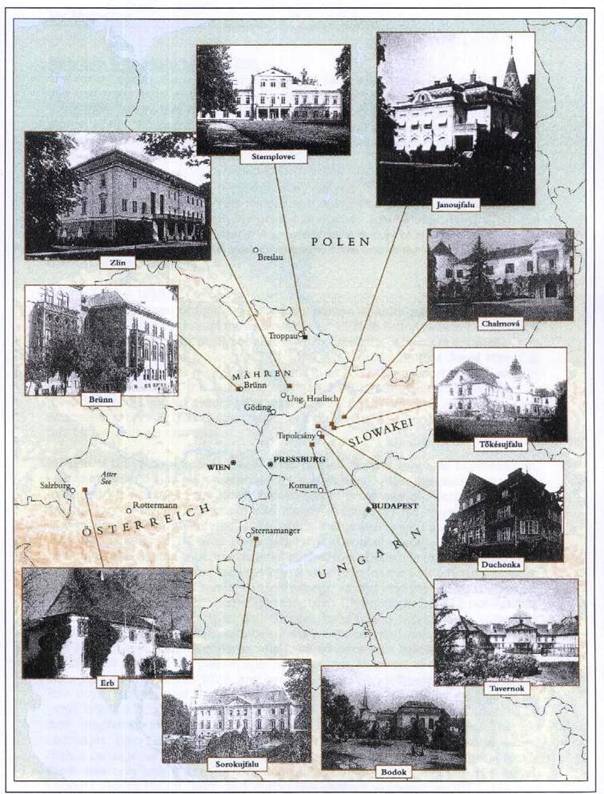

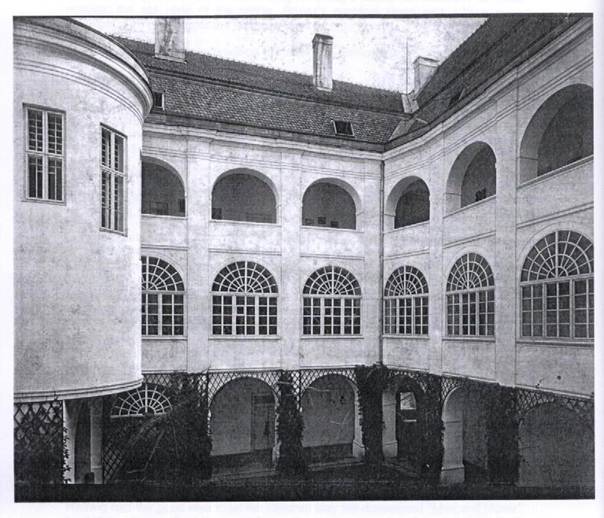

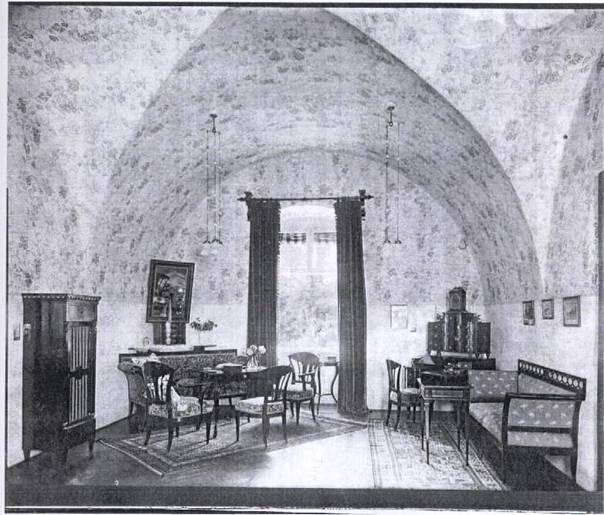

1/ BRÜNN, Kiosk 11, bought by Stefan Baron Haupt von BUCHENRODE in 1914. Rebuild by the well-known architect Leopold Bauer*.

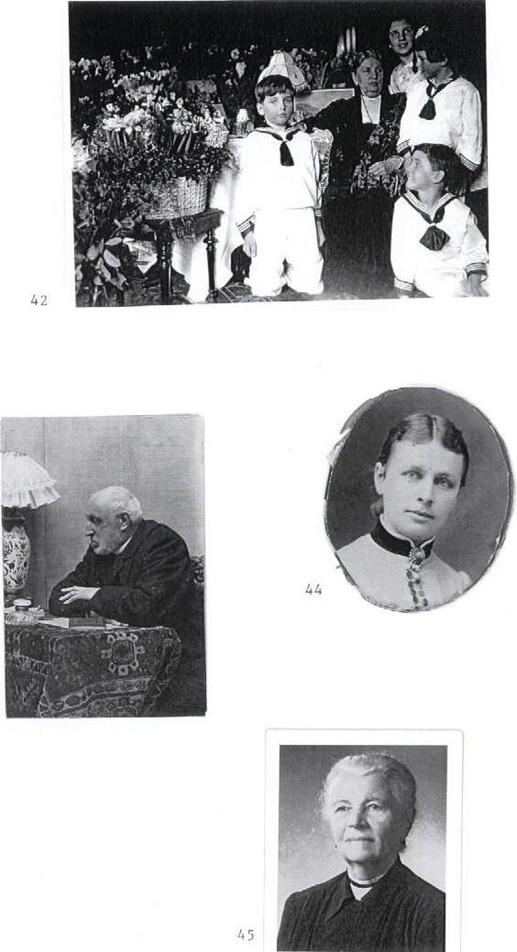

2/ ZLIN, bought in1860 for 470.000 Gulden by Leopold Alexander Haupt,

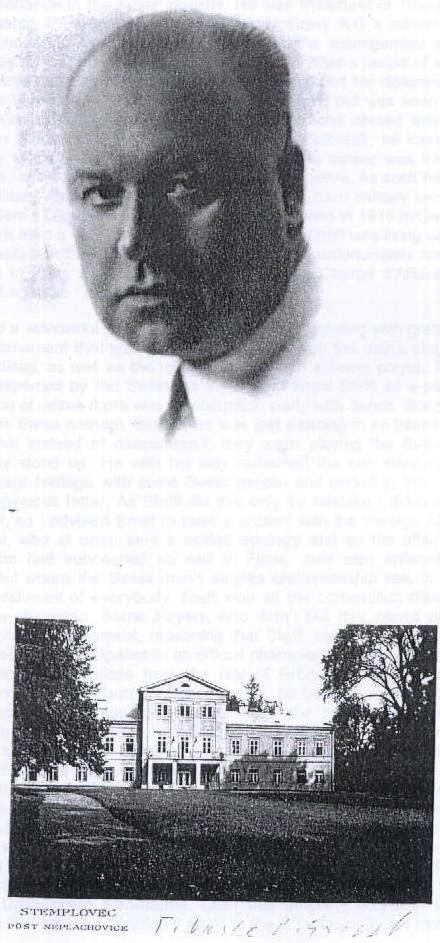

sold in 1929 for 11,950.000 Kč.crowns by Stefan Haupt v. Buchenrode.

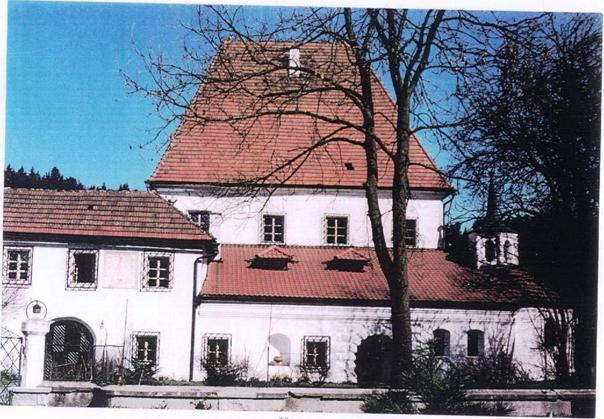

3/ STEMPLOWITZ, bought by Ernst von Janotta and his wife Dorle (renovation in 1930*)

4/ JANUFALU, bought by Poldi Haupt Stummer and left to his daughter Gertrud. The Nesnera’s home after 1918.

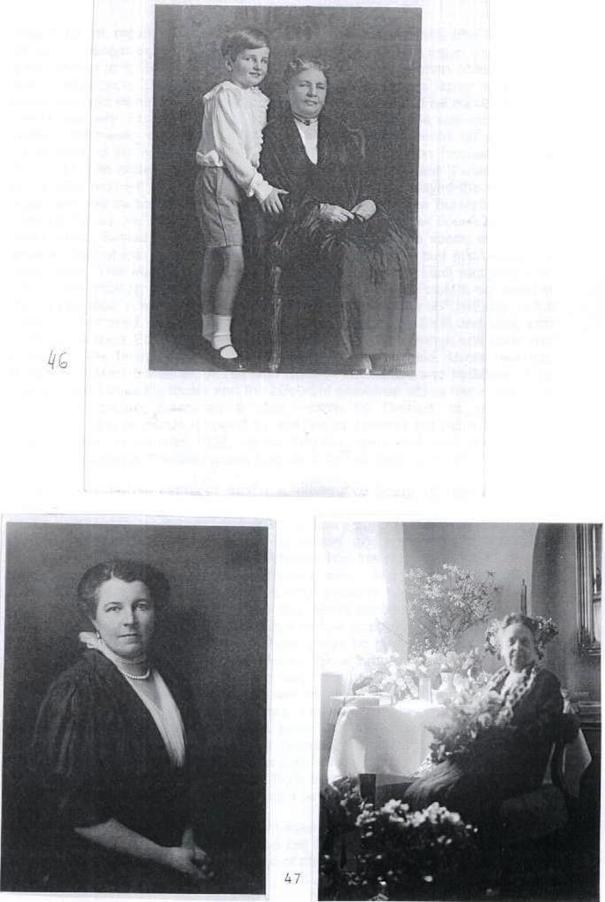

5/ CHALMOVA, bought by August Haupt-Stummer in 1930, (reformed in 1935*) it was their home after they left the southern wing of TAVARNOK.

6/ TÖKÉSUJFALU (Klatova Nova Ves), bought by Leopold Alexander Haupt in 1884 for 280,000 Gulden for his son Poldi when he married Auguste Stummer v. Tavarnok. Later left to Poldi’s daughter Carola. The Thuronyi’s home.

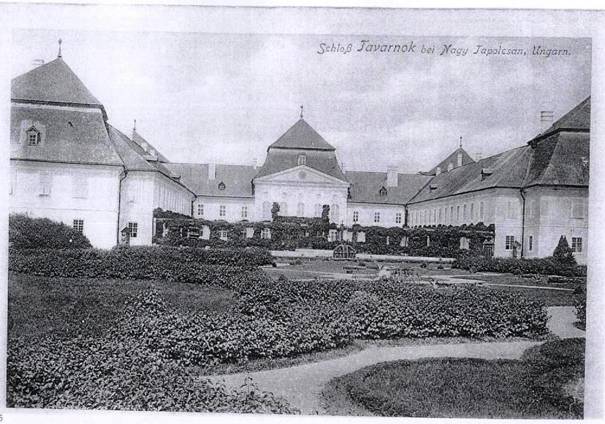

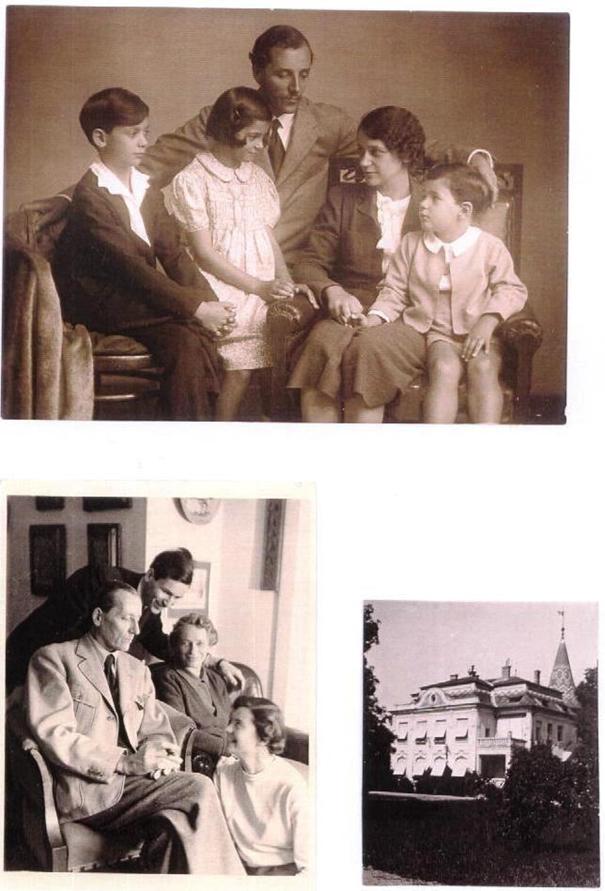

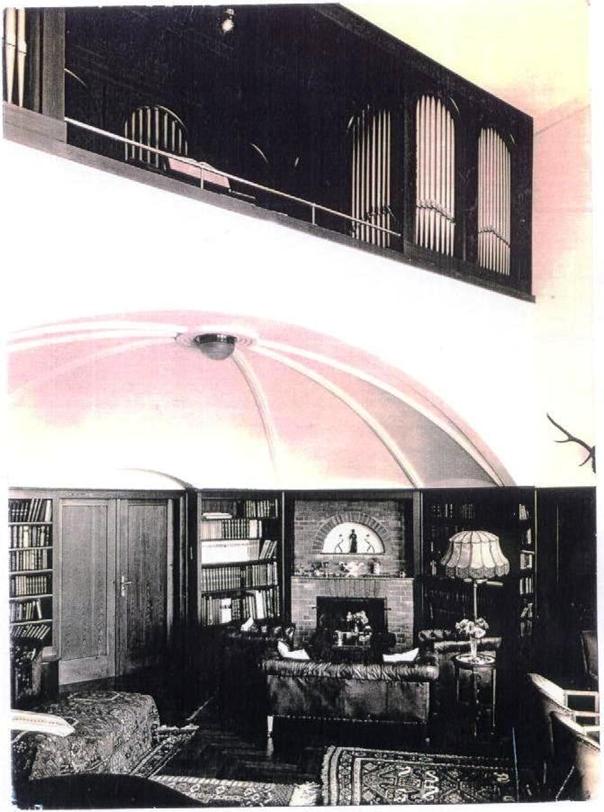

7/ DUCHONKA, was bought in 1928 and build by Stefan Haupt v. Buchenrode for his daughter Liesl, with a build in organ, in 1930/31

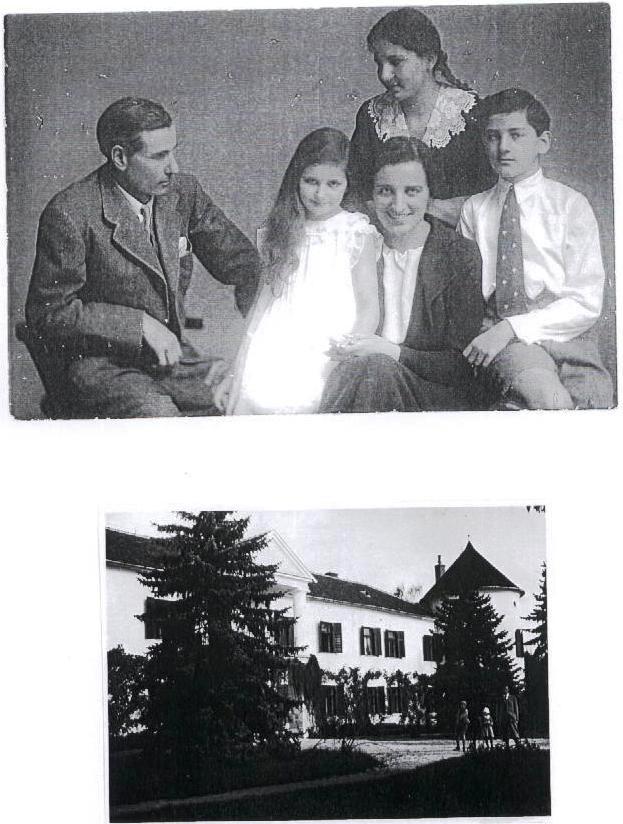

8/ TAVARNOK, bought by August Stummer in the late 1870’s; was later Poldi and Auguste’s home, and their first grandson Béla was born there. After 1928 Leo Haupt Stummer and Leni’s home, where their children: Leo, Pupa and Ernsti were born.

9/ BODOK, bought by Alexander Haupt Stummer in the late 1870’s. He was Lucia Sheaffer (Pretis de Cagnodo)’s great grandfather.

She lives now in U.S.A. (Maine and Arizona)

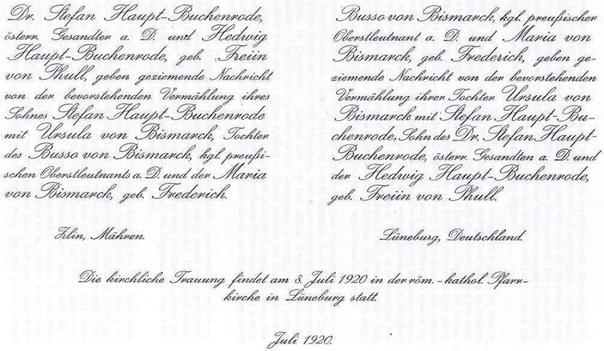

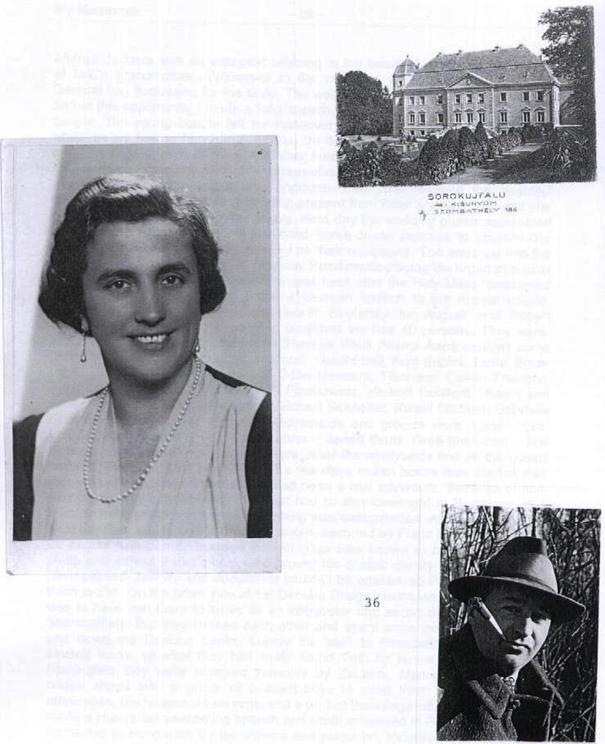

10/ SOROKUJFALU, bought in 1916 by Stefan Haupt v. B. for 3,800,000 crowns and donated to his son Steffi at his marriage with Ursi in 1918 (our home in Hungary, renovation in 1926).

11/ ERB, bought by Ernst Haupt Stummer in the late sixties.

Mährisch – Rotmühl 1676 – 1805.

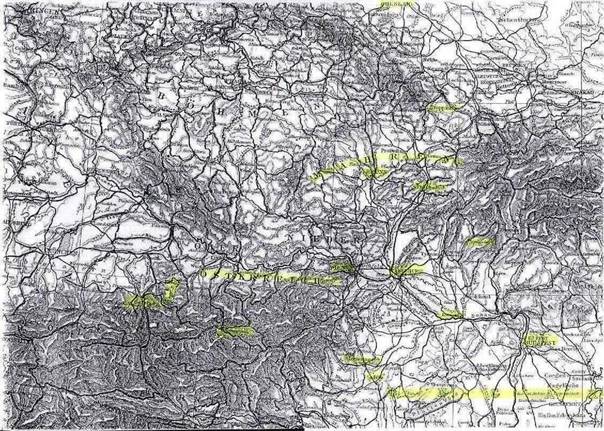

Our family comes from the northern part of Moravia, Mährisch–Rotmühl, where you can trace them in the church-books up to the year 1676. They surely were living there before this date, but the registration books were destroyed during the storms of the “30 years war.” Our forefathers owned a large farm and also ran a “bleaching” and “pressing” operation for the linen weavings, common in this part of the country.

At this stage of a humble prosperity they stayed for over 200 years, until the troubles of the Napoleonic Wars shook them out of their quiet life and forced them to more and harder activities. My great-grandfather Josef Haupt, born 1763, got from the Austrian ministry of war a large order for a supply of linen for the Austrian army and consequently could already employ at the end of the 18th century a great number of home-workers.

Brünn 1805 – 1899.

For the management of this large trade the village of Mährisch–Rotmühl was too far away and so Josef Haupt moved in 1804 or 1805 to Brünn, where he bought a house in Fröhlicher Street. Since this time the military orders grew steadily and were, after the Viennese Congress of 1815, so remarkable that Josef Haupt at this stage employed all over Moravia more than 6,000 home-workers. He died in 1816. His enterprises, the farm and the bleaching in Mährisch-Rotmühl, went to his eldest son Leopold Georg who was only 20 years old. The inheritance was estimated to be 700,000 Gulden, Viennese currency. And Leopold Georg had to pay off his brothers and sisters.

In spite of his youth, Leopold Georg soon proved to be a very able businessman, who managed to run his enterprises on a high level. After the peace treaty, he extended his market to the newly gained Italian provinces of Austria, opening a new factory in Milan. This boom was mainly reached by his invention of a new way of packing the military-belts, by which the government could save several 100,000 Gulden, so he was rewarded for it. Leopold Georg married Therese Lettmayer, the daughter of an important leather industrialist, in Brünn in 1826. The Lettmayers owned, besides their factory, a very nice house with a large garden in the suburb Kröna, with a summer resort aspect. At that time the old Mr. Lettmayer was already dead and his widow Therese, born Ehrenberger from Upper-Austria, who had inherited this considerable fortune, lived in the Kröna house. She was considered by all her acquaintances a very resolute and able businesswoman. She had not less than 13 children who were all deceased before her. Only two of her children reached the marital age: her daughter Therese, who married Leopold Georg Haupt and died in 1828, and her son Franz, who left behind a wife and two little boys, Richard and Eugen, when he died in 1846. His widow married a few years later the governor of Moravia, Baron Poche. Her two sons were adopted by their stepfather and got the name Poche Lettmayer. The old Mrs. Therese Lettmayer, born Ehrenberger, died in 1850 on a trip to the spa Carlsbad, falling from a carriage, at the age of 68. At the time of her death, out of her great family there was only one grandson left, Leopold Alexander, 23 years old. His father, Leopold Georg Haupt, had died during the cholera epidemic in 1851. He was married for the second time in 1834 to Emilie Schöll, the daughter of a cloth manufacturer. They had nine children, two boys and seven daughters; we will be referring to them later on. His son, Leopold Alexander, my father, lived with him till his second marriage. Then he moved to his Grandmother Therese Lettmayer’s house in the Kröna where he stayed till she died. Both his grandmother and his father died within a short time and so he suddenly inherited the whole Lettmayer fortune and half of the Haupt’s.

Leopold Alexander’s task was pretty hard, as he was not an expert in leather manufacturing. He therefore decided quickly to wind up the Lettmayer inheritance and to limit his activities to the linen manufacturing of the Haupt’s inheritance. The freed capital he invested in a banking business, which he opened in the beginning of the fifties in Brünn. The rate of interest in Austria was, after the troubles of the revolution in ’48 and the wars with Hungary and Italy, very high and offered owners of free capital very good chances of profit. The rate of government bonds was extremely low. The bad financial situation of Austria didn’t keep my father from buying a great amount of these bonds. My father at that time was already considered a rich man and wanted to set up his own house. His choice fell on Anna, the 19-year-old daughter of a well known lawyer in Brünn, Dr. Schlemlein, from the Supreme Court of Judicature and his wife, Henriette Schlechta von Vsehrd. The wedding was on January 23rd, 1858, in the episcopate chapel of the cathedral of Brünn. The political confusion of this year didn’t make it advisable to go for a honeymoon abroad, so the young couple decided on a trip to the Haupt's house in the Kröna. There they also opened their household after Leopold Alexander’s stepmother moved to her newly-bought villa in Schreibwald Street.

At that time the constitutional movement in Austria started and the governor of Moravia let my father confidentially know that the government would be happy if he would take part in this movement and for this purpose would buy a property in Moravia. My father didn’t oppose this suggestion of the government; as a matter of fact he thought it would also be a good investment for his free capital. Among several offers there was the property of Zlin, in Moravia, which belonged to two eccentric bachelors, the Barons von Breton. The transaction couldn’t be realized, as the Bretons’ demand was too high. But as they were in financial difficulties they sold the property to the leather manufacturer Bergen in Brünn in the same year, 1856, who then sold within two years to Count Günther Stollberg. But as he died within a year, his widow called again on my father, offering him the property. The negotiations were satisfactory and my father bought the 2,400 ha property of Zlin for the price of 470,000 Gulden in July 1860. The estate was in poor shape as the Bretons were missing capital to equip the property properly in a modern way. The productivity of the forest, which was mainly beech trees, was badly handicapped by a very unfavorable contract of delivery with a timber dealer of Vienna. This contract obliged them, through many years, to deliver several hundred wagons of beech logs to Vienna. This unfortunate contract could be ended only after a long process. The farmbuildings of Zlin, Mlacov, and Cäcilienhof, as well as the castle, were in poor condition. Although the Bretons had started a renovation in 1850, they were forced to stop half way for monetary reasons. My father, who was not a passionate farmer or forester, didn’t change much of this situation in the beginning and started a partial renovation of the castle only in 1874.

On January 12th, 1859, their first son was born and was baptized with the name of Leopold Eugen (called Poldi). He was followed, after a long pause, December 5, 1866, by a daughter, Marianne, and on October 27th, 1869, a son, Stefan Viktor, the author of these pages. The purchase of the property Zlin brought quite a change in my parents’ day-to-day life. Until now they had stayed throughout the year in their town apartment except for a few weeks in summer on their estate in Rotmühl. From now on, the castle of Zlin, with its beautiful park and the charming surroundings, was chosen as their summer resort. As my father was no more interested in the estate of Rotmühl, it was sold soon after 1866. Next to be sold was the “bleaching” in street Zeile in Brünn and the big garden at the Kröna was divided into lots and built up. After this, the holdings of my father were only the houses in Brünn, the banking business and the estate of Zlin, on which he now could focus all his attention. Besides that he dedicated his time to public affairs. He was elected to the municipal board of the city of Brünn and a member of the chamber of commerce.

In 1864 he founded with his brother-in-law, Gustav von Schoeller, and some other prominent industrialists from Brünn the Escomptbank. He was elected to the administrative board. He now liquidated his own bank business (1865) as the threatening war with Prussia left the financial situation of small banks quite unsafe. Nevertheless the war of 1866 brought no change for the worse to Leopold Alexander’s pecuniary circumstances; not even the great breakdown of the stock exchange in 1873 modified his financial situation. This one had only disadvantageous consequences for his half sisters, who by making wrong speculations lost most of their fortunes. Indirectly these changes had an influence on my father as they supported his tendency of great economy. My father’s opponents often accused him of being paltry. But this reproach could be made only for small affairs. In important affairs he was always very broad-minded. For example, in the ‘60s he donated more than 100,000 florins for scholarships to small tradesmen and poor scholars. Besides that he left in his testament 100,000 crown to the city of Brünn for the establishment of a children’s recovery-nursery in castle Kiritein, next to Brünn.

Leopold Alexander was always on very friendly terms with his stepsisters and one of the sisters always was invited to spend the summer in Zlin. As these very dear aunts had a great influence on us children, their life should be mentioned here, too. They were all good looking and elegant figures who knew how to attain standing in society and were very popular, especially in officers’ circles. All married officers except one. This one was Leopoldine, born in 1835, married in 1855 to Sir Gustav von Schoeller, one of the greatest cloth manufacturers of Brünn. She was a highly educated and fine lady, but she suffered from poor nerves, - nevertheless she reached the age of 89 and left behind two sons and five daughters:

Leopoldine, (Putzi) married Carl Mühlinghaus, Brünn,

Marie married Gustav von Paumgarten, Brünn,

Sofie married Johann von Pfefferkorn, Brünn

Lisa married Alexander von Schreiber, Vienna,

Gustav married the actress Anni von Lighety, Vienna,

Hedwig married Colonel Géza von Szüts-Tasnád, Vienna,

Friedrich married Jovy von Bogdan.

The second stepsister was Sofie, born 1837, married to Baron Stanislaus Bourguignon. She died at only 23 years of age, from diphtheria, and left behind two daughters. Bourguignon soon married again, Princess Salm, whom he divorced two years later. His two small children were lovingly accepted and brought up by their stepmother. The elder one, Amelie Bourguignon, married Baron Wyttenbach, landowner in Styria. The second, Hermine, was taken in as a grownup girl, by her aunt, Adele Krieghammer, and married Count Jean Lubienski, a ”Ulanen” lieutenant, in Lemberg in 1890. This couple had three children: Stanislau (Stas), Jean (Jas) and Constance (Kocia). Hermine (Minni) Lubienska died in 1946, at the age of 86, in Pápa (Hungary), where she lived after her husband’s death with her daughter.

Adele, our favored aunt, born 1838, married in 1858 in Brünn an officer called Grognier d’Orleans, but they divorced after a few months because of his coarse character. She thereafter lived with her younger sister Marie in Vienna.They both spent a very jolly life. Adele was married a second time to Edmund Baron von Krieghammer, major in the 5th Dragoon Regiment. Later he was commander in charge in Krakow and from 1895 to 1902 Austro-Hungarian minister of war. He belonged to the very intimate circle of Emperor Francis Joseph, and was a steady guest at the stag hunting in Ischl. At one of these hunting parties in 1906 Edmund Baron von Kriegshammer died. He left behind, besides his widow, a daughter Olga and a son Kurt, Lieutenant in the 5th Dragoon Regiment. Aunt Adi stayed on in Vienna and, till the First World War, always spent a few weeks each summer in Zlin. As through the years of war living got more difficult in Vienna, she and her daughter accepted an invitation, of my brother Poldi, to Tavarnok. After the war he offered her castle Bossany as a place to stay. There she was lovingly nursed by Olga for another six years and finally died in 1925, to our great sorrow.

Marie (Riri) was born 1840 in Brünn and married in 1857 2nd Lieutenant Eduard Friedenfels, who died in 1859 during the battle of Solferino. He left behind a daughter, Marie (Mitzi), and a son, Eduard, posthumous, born in 1859. Marie was living after the death of her husband with her sister Adele in Vienna, where after a few years she married Baron August Normann, 2nd Lieutenant in a cavalry regiment. Some misunderstandings were the cause of their separation for a couple of years, but after reconciliation they lived, till their death, in a happy matrimony. They were both very good-looking people and very popular in the society of Graz. It was said that Aunt Marie looked very much like Empress Elisabeth of Austria. She died in Graz in 1900.

Carl, born 1842 in Brünn, entered the army in 1860, after finishing his studies, and was a lieutenant in a “huszár” regiment. He participated in the battle of Königgrätz and was wounded in his upper leg. After he recovered, he left the army and bought the estate Straussenegg near Gilli in Southern-Styria. His mother, who after the marriage of her youngest daughter, Julie, stayed alone in the Schreibwald Villa at Brünn, moved to his place. The house at Brünn with the nice garden was sold and she stayed at Straussenegg, where her daughters went to see her, till she died in 1883. Carl remained a bachelor but had a love affair with an actress of the German Theater in Laibach. He had two children from this liaison, Carl (Cari) and Margarete (Gitty). As the mother of his children was already married, but divorced, he couldn’t legitimatize his children by a marriage with her. Then Carl made a petition to the emperor to get the legitimization of his children through an imperial decree. Considering his war-indemnity and his decorations (Iron Crown), his petition was granted by decree. Uncle Carl was a famous horse breeder and expert; this brought him a nomination of the government of Styria. As a reward for his efforts in this field he was granted knighthood with the predicate “von Hohentrenk.”

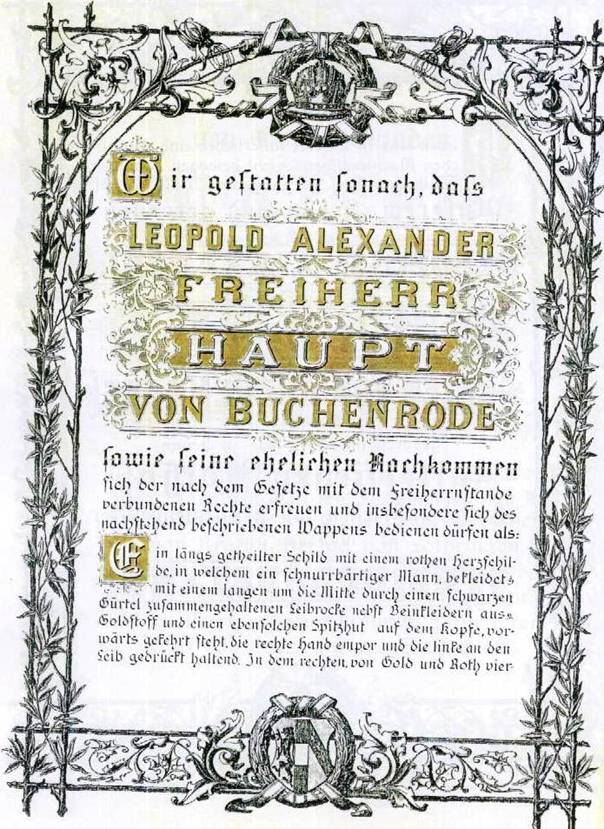

My grandfather, Leopold Georg Haupt, had a younger brother called Julius who owned a signet ring with an old coat of arms showing an upstanding man in a shield. Carl Haupt wanted to use this old coat of arms for his patent of nobility. On searching for the origin of this coat of arms, it was found that an ancient noble family Haupt seated in Saxon (Germany) uses the same coat of arms. The consent of this family had to be applied for to transfer this coat of arms to Carl Haupt. In the course of negotiations they agreed with Carl bearing this old coat of arms and expressed their opinion that the Haupt’s Austrian line originate from the same family as the Saxonians.

Carl died in 1916 in Straussenegg. In his testament he indicated me as the guardian of his children Cari and Gitty. As Straussenegg was very near the Italian battlefront and there was nobody to be in charge of the property, I sold it in 1917 and invested the money safely. Soon afterwards Cari entered the Austrian-Hungarian army, and after the end of the war married in Budapest a Baroness Dittfurt, whom he soon divorced. Gitty stayed quite a while in my house, traveled a lot, and married Mr. Klasing, co-owner of the well-known publishers “ Vellhagen and Klasing” in Berlin.

Therese (Thesy), born 1844 in Brünn, married in 1869 navy Lieutenant von Henneberg, who was aide-de-camp to Tegethoff during the navy battle of Lissa in 1866. After the marriage, he quit the navy, and settled down with his young wife in Cilli. There were born their two children, Nanine and Erni. Soon after Henneberg developed an illness in his spinal cord and in consequence became blind. Unfortunately his wife died even before him, in 1897. Nanine nursed her father until his death a few years later. Than she went to her brother’s place in Transylvania, where he was serving with a hussar regiment in Hermannstadt. Soon she got engaged to Silvio Spiess von Braccioforte. The wedding was celebrated in Zlin, in our place, in 1902. This couple had four children: Therese married Franz Vermeulen, a Dutchman, and professor at the Academy of Arts in Haag. Hans married a Czech called Mila Vavrik, divorced, and lives now 93 years old in Linz; Silvio married during the Second World War in Germany Helga Ries. Margarete (Putzi) married Tibor de Mérey, a Hungarian, who lost his life in 1945 escaping from the Russians. She was kept in a camp in Bohemia with her two little children, till her brother-in-law, Gyuri Mérey, could bring her to Switzerland where she learned of her husband’s death. *[She now lives in Yverdon, Switzerland with her daughter Desiré, who is a widow of Prince Friedrich Lobkowicz (her e-mail is: dlobkowicz@bluewin.ch ). Her son Peter Mérey works in Geneva.] Their father, Silvio senior, commander in charge of an infantry regiment was killed in the first winter battle in the Carpathians in 1915. Post-mortem he was decorated with the Maria Theresa Order. Poldi and Auguste took care of the orphans and invited Nanine to live in Tavarnok with her four children, where she stayed till 1949 even after the marriage of all of her children. When the circumstances in Slovakia were unbearable, and the castle inhabitants also had left, she decided in spite of her age to move to her daughter’s in the Haag, but there she soon died, in April 1950.

Gabriele, born 1847, married 1867 to Stefan Count Schlippenbach, a colonel of an Austro-Hungarian hussar regiment. They had two sons: Wolfram, born 1868, was killed as a German officer in the Herero-war in German-West Africa and Parcifall (Percy), who emigrated to Chile working as cabin boy on a steamship and not heard of again. The Schlippenbach couple got divorced; Gabriele converted to Protestantism and died in 1917 in a women’s home in Silesia (Germany).

The youngest daughter Julie was born in Brünn in 1848 and was married in 1868 to Prokop von Zeidler, 2nd Lieutenant in a Dragoon Regiment. They had four children: Alfred born in 1869, Egon in 1870, Helene in 1874 and Lilly in 1882. Both sons were soldiers in the 25th Fighter Battalion. Both completed the military high school, were appointed to the General Staff and achieved high missions. Alfred advanced in the 1st World War to field marshal-lieutenant, but after the war quit the Austro-Hungarian army. He was married to Jolán von Gábor and had two daughters. Alfred died in Vienna in November 1950. Egon was appointed chief of Emperor Karl’s military office. He was an ardent Austrian patriot and took the breakdown of his country badly to heart; when he then also lost his wife (Baroness Vivenot) he committed suicide in his despair. Helene and Lillie stayed unmarried and are living (1951) in Graz. Aunt Julie Zeidler died in 1922 in Graz.

The last child of the couple Leopold Georg Haupt and Emilie Schöll was a boy, called Richard, born in 1851 after his father’s death. He died as a child of ten from diphtheria, at the same time as his sister Sofie Bourguignon.

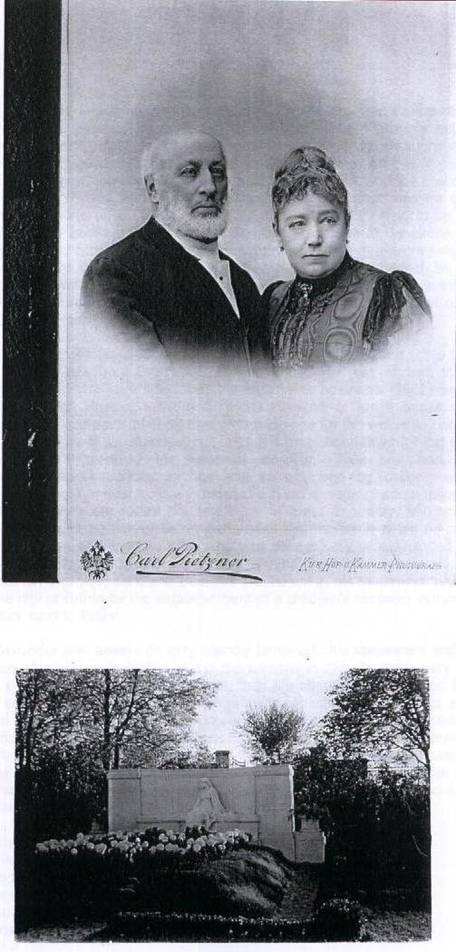

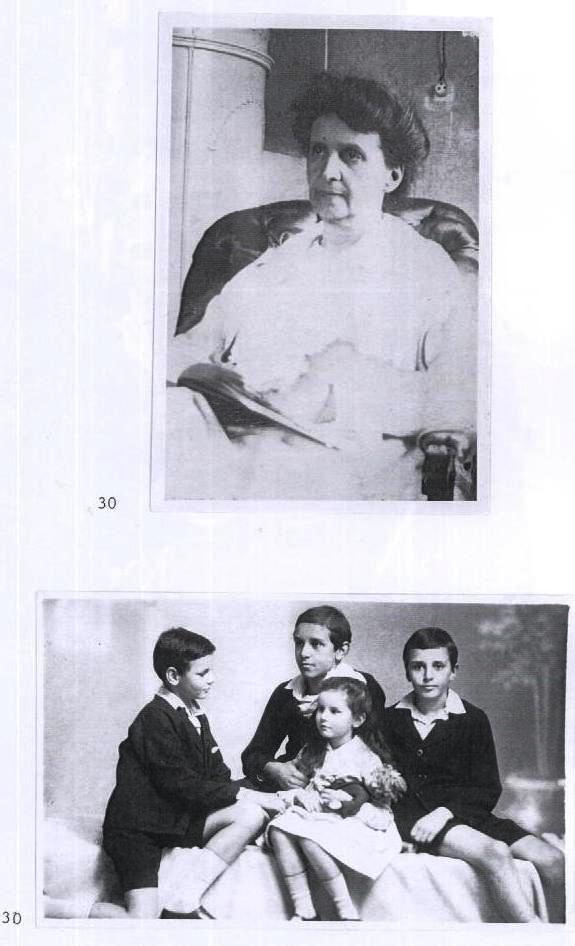

After this digression we come back to my father Leopold Alexander Haupt. He was an odd person, whose feelings had suffered a lot by the early loss of his parents and all of his uncles and aunts. He avoided all sociability and had disdain for all conventions, which you could even see in his clothing. His way of life was very Spartan and he hated any luxury; although he could have afforded any comfort, his way of living stayed very austere. In this way he also influenced his children, whose education, by the way, he left to his wife. My mother was the personification of kindness, whom we children loved in a divine way. She took care of the poor and sick people on the property Zlin in a charming way, and spent most of her income on charity. She was a very pious woman, but far from bigoted; this was the way she educated her children and influenced especially my religious feelings, as I was her youngest child.

There existed a very tight and loving union between my sister Marianne and me, which still was increased by the compassion I had for her terrible sufferings, caused by a meningitis in her early childhood. Nevertheless we spent a very happy childhood together, especially in summer in Zlin. Wintertime Marianne mostly spent in a southern climate. These trips took her to southern France and Italy, where in Rome she was delighted by the fine arts. On these trips she was accompanied by one of her invited cousins; mostly it was Nanine Henneberg, and her truthful attendant, Marie Holweck. Marianne was a kind, good, noble-minded person who endured her suffering, which imposed so many privations on her, with a remarkable equanimity. Her life was dedicated to alleviating the misery and distress of her fellowmen.

Very different was my relationship with my brother Poldi. As he was 11 years older than I was, I had no childhood remembrances of him. From hearsay, I knew he was not very fond of books - he had failed to pass his exams at high school in Brünn, whereupon our father sent him to a very good and severe boarding school in Vienna. But his stay there didn’t last long. As he didn’t like the severe treatment and the bad food, he decided with some other like-minded fellows to escape from the institute, which they succeeded in doing on a stormy night. His arrival at home didn’t receive great welcome. To return him to public school didn’t seem advisable, so it was decided to engage a private tutor for Poldi to continue his studies. Soon the right person was found; it was Josef Gottwald, himself a medical student who because of financial problems had to quit his studies and who had already been very successful in two former aristocratic homes, at Count Widmann’s in Wiese and Count Zierotin’s in Blauda. This Gottwald was a good example of a tutor, a very well educated, severe, law-minded person. But aside from being a humble and diligent schoolmaster, he nevertheless had the fault of too much pedantry, which prohibited him from earning his pupil’s love. Yet he succeeded in getting Poldi through his remaining classes of high school and baccalaureate. Poldi then carried courses at the Technical University of Brünn and founded there the Corps Marchia. The following year he went to the Technical University of Prague where he followed the chemical courses. Besides that, he participated in a lot of sports and was a very able, strong, muscular gymnast and a good fencer. He had a good sense for arts and a lot of smaller talents, which only needed to be trained. He had a fine musical ear, a nice tenor voice, and played cello and piano. He also was a good designer and would have been a good architect if he could have dedicated his studies to that. Our father didn’t want him to be an architect, because he wanted him to be a cloth manufacturer. This was understandable due to the importance of the textile industry in Brünn. Next Poldi was sent abroad to study textiles in Reims, where he stayed with the manufacturer Marteau’s family. Marteau’s wife was a very beautiful German lady and they had a very musically gifted ten-year-old son. Later he grew to be the very famous violin virtuoso Henri Marteau, with whom Poldi stayed in contact till his death. From Reims Poldi went one year later to Lille and from there, after a short stay, to Barcelona where he ended his practical formation.

Let’s get back to my own person. As I saw the light on October 27th, 1869, in Brünn, our old family doctor, Dr. Linhardt, said jokingly, as he looked at my uncommonly great head: “This one either gets hydrocephalus or he will be a genius.” I think neither of the prophecies came true; neither did I get a hydrocephalus nor was I a genius; I had to be satisfied with an extraordinary memory and a fast comprehension. This way I could manage my homework at high school in a very short time; although I had, besides school, French, English, Czech, piano and violin classes, I never used night hours for my studies. My teachers didn’t want to believe that I could manage all these classes and were foreseeing my failure. As I finally received my excellent grades as 3rd in a class of 39, I got credit for the rest of my school years and no warnings anymore. Of course I had no time left over for sports. Unlike my brother Poldi, whom as a child I admired for his strength, I wasn’t so strong and was not a good gymnast; but I was a quite good horseback rider and fencer.

My childhood memories go very far back and are mostly connected with the summer months we stayed in Zlin. So I remember very well the day, although I was only 2 ½ years old, when the stage-coach which made the connection to the train station in Napajedl, 15 km away, stopped at the gate of the park. Out came a lady from Alsace, whom my mother had hired, who introduced herself as the French governess Marie Holweck. The first impression for us children was crushing, because she was rather ugly and had an unusual beard that disfigured her face. She understood no word of German, so communication, for us children, was rather difficult in the beginning. Nevertheless, this young girl managed this difficult situation and in a very short time gained not only our love but also the love and confidence of my parents. Thereafter she stayed for 50 years uninterruptedly in our family. I was completely given over to her nursing and teaching of French, and she did that so well that after a year I was babbling just as well in French as in German.

As long as I hadn’t entered high school, I spent every summer with my parents and my sister at Zlin. My playmates were at that time the sons of the estate functionaries, a son of the mayor of Zlin and I didn’t disdain the company of some employees’ boys. Besides that, I found the company of a little French boy, who was temporarily sidetracked to Zlin with his mother and sister. His father, Mr. Robert, was manager of the Viennese branch of a French shoe factory. He had connections to Zlin, which at that time could already be called a shoemakers’ town because it had within 2,000 inhabitants 75 shoemakers’ workshops. Mr. Robert had a foreman called Slamena, who was from Zlin. Mr. Robert’s little son André had a natural defect of a shorter leg, which always had to be put in a splint. Viennese doctors advised them to strengthen him in fresh forest air. Slamena had called Mr. Robert’s attention to Zlin, famous for its healthy air, and that’s why he was renting a house on our property and moved his family to Zlin. They visited my parents and soon a friendship developed between the two children of same age.

In the neighborhood I had as playmates only the sons of Count Sternberg in Pohorelitz, who were of the same age. One of them was Moncsi Sternberg, who later on gained a rather dubious celebrity. He at that time was already a violent guy whom, because he was teasing me too much, I thrashed in the presence of both of our parents. For this I got appreciation from his father. Among our neighbors there were still Count Stockau in Napajedl and Baron Stilfried in Wisowitz, but with them we had no special contacts. We did have contact with Mr. Von Gyra in Klecuvka, mainly because of my mother’s friendship to Mrs. Von Gyra, and our families got better acquainted. Katherine von Gyra was a born Zechani, niece of the ambassador to Greece, Baron Sina in Vienna, who gave her as a wedding present the estate Klecuvka, in our very near neighborhood. Her son Konstantin later married Mimi Baroness Isbary from Vienna, with whom Hedwig and I were on very friendly terms. Also, their only son Georges was a frequent guest in our house.

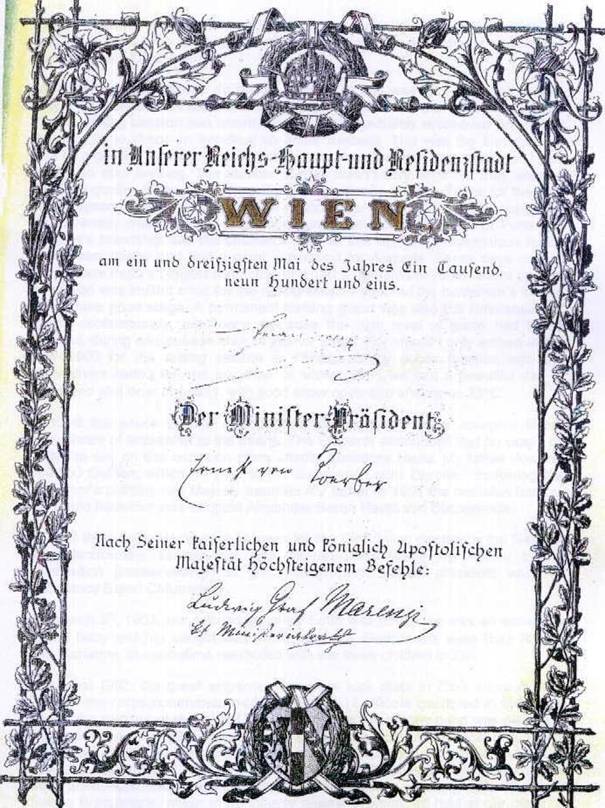

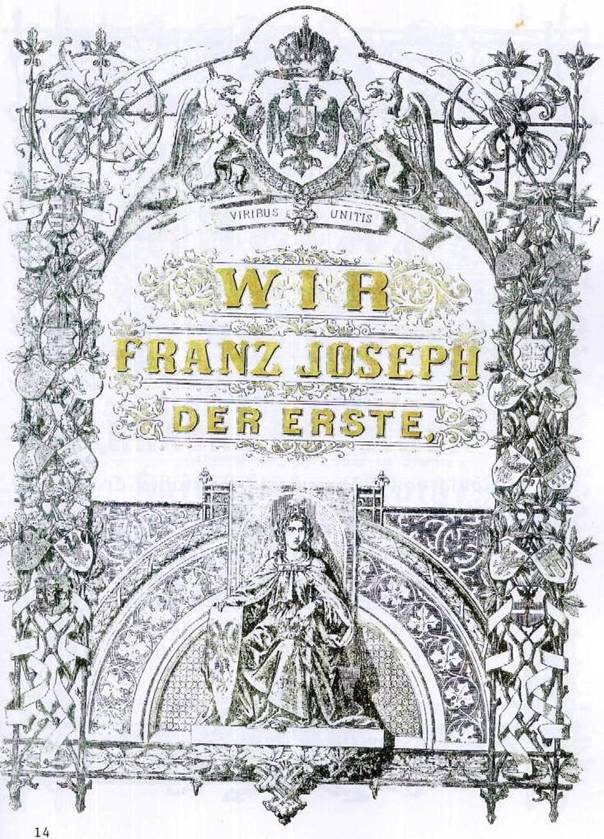

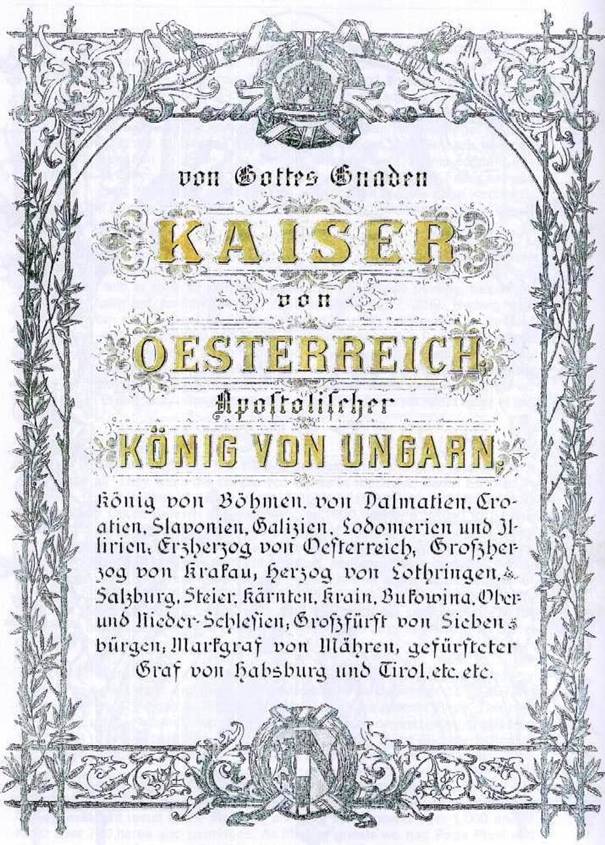

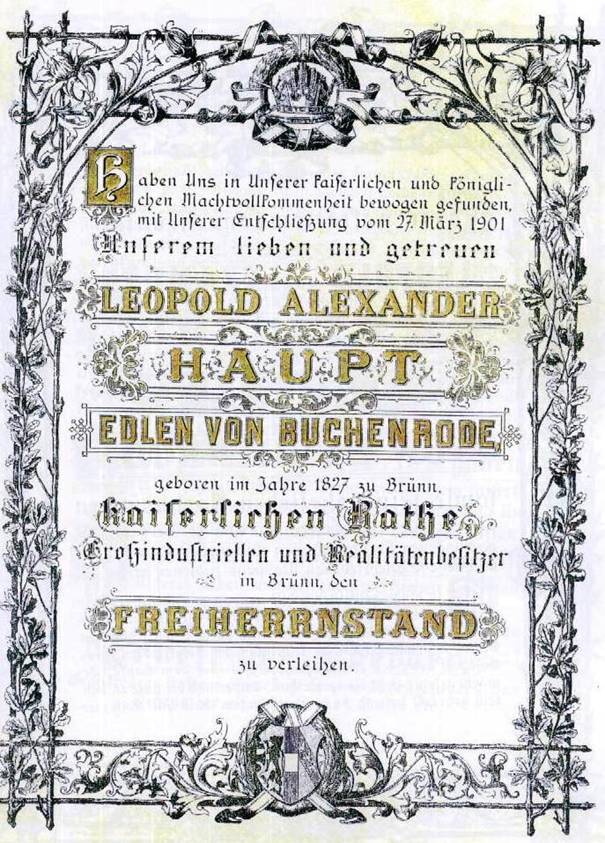

In 1874 the Emperor Franz Josef awarded my father the nobility, with the title von Buchenrode. It was in appreciation of his merits, which he gained as a longtime deputy of the landowners in the Moravian country council, as a member of the chamber of commerce and the municipal council of the city of Brünn, as well as through many charity foundations.

On October 1st, I started first grade at the German Gymnasium in Brünn. As our home in the Kröna was rather far from the school, I couldn’t come back for lunch. It was decided for me to take my lunch, during school time, with Mrs. Fanny Gottwald. She was a former helper at my mother’s household and married in 1878 Poldi’s tutor, Josef Gottwald, who meanwhile had a job as a librarian at the German University in Brünn. They had a nice home, quite near to the Gymnasium, so I could have a rest and study with Mr. Gottwald. This situation went on till Mr. Gottwald’s death in 1886.

At the end of April 1883, as all was prepared to move to Zlin, I came home from school with a shivering fit. The fever climbed to 41 degrees and I lost consciousness, which I recovered only nine days later. When I woke up after the crisis, bathed in sweat but saved, I was told that the doctors had diagnosed typhoid fever and pneumonia. I was released from school for the current period. My recovery was fast, and I could be taken to Zlin a few weeks later. To make up for the missed school time, my schoolmate Viktor von Geschmeidler was invited to Zlin and henceforth was a permanent vacation guest. In the following year my second school friend Franz Kreuter joined us, too. He was very musical and an excellent violinist. I also made progress with my violin, so we decided to form a string quartet. Kreuter played the first violin, I the second, and two other mates, Bayer and Kafka, played the cello and viola. We took great pleasure in these musical evenings at my parents’ place in Brünn. To satisfy our literary demands we founded, on suggestion of our schoolmate, Egon Zweig, a readers' club. The members, naturally only males, met regularly every Sunday afternoon to read dramas with distributed roles. This readers’ club was highly esteemed by all colleagues and often-violent struggles were fought for its presidency. The female roles were also represented by boys, and so it happened that a very ugly Jewish boy, but excellent declaimer, called Pollach was given the role of the Virgin of Orleans and of Desdemona, which by no means interfered with our enthusiasm.

In 1882 Poldi came back from his study tour in Spain and France and started to work as a volunteer in the worsted-spinning mill. The work there didn’t appeal to him and he was looking for distraction in social life. Among the families he met there was the machine manufacturer Ernst Krackhardt’s, whose two eldest daughters, Marianne and Helene, were good friends of Auguste, daughter of the great sugar industrialist Baron August Stummer of Tavarnok. The latter was born in Brünn and a good friend of my father Leopold Alexander Haupt. He married in 1860, in Hamburg, Betty Melchior, a former naïve actress of the City Theater of Brünn. She was called to a theatrical engagement in Hamburg and thereafter was living there with her mother.

The brothers Carl, August and Alexander owned the company “Carl Stummer,” in Brünn, which was managing, for many years, the national salt monopoly of Austria. The field of activity got narrow for the fervid activity of August Stummer and soon after the end of the Italian war in 1859 he moved, with his brothers, to Vienna. There they renounced the management of the salt monopoly and turned towards the sugar industry. After the early death of the eldest brother Carl in 1873, August was the leader of the great companies founded by him. After just a few years, through skilful transactions, he was able to found the sugar industries Pecek in Bohemia and Göding, as well as Oslawan in Moravia and to buy the two big estates, Tavarnok and Bodok, near Tapolcsány. To take better advantage of the large beech forests of Tavarnok, the sugar factory was established and was run (mentioned here as a curiosity) by firewood. At the same time a sugar refining plant was set up in Tyrnau. A few years later, by request of the Hungarian government, the great sugar factories of Mezöhegyes and Kaposvár were established as a joint-stock company. Fifty percent of the shares were held by the Hungarian Government and 50% by the Carl Stummer Co. In appreciation of the great merits he had achieved with the Hungarian economy August and his brother Alexander were awarded the Hungarian barony. Poldi got engaged in summer 1884 to Auguste, daughter of August and Betty Stummer. The engagement was celebrated in the castle of Tavarnok on July 15th and the wedding took place in Vienna on November 16th of this same year. As Auguste had no brothers I was asked to be the best man, although I was at that time only 15 years old. For this occasion I got a tailcoat and I admit to having been very proud of it.

Poldi received from our father the estate Tökés Ujfalu, 1,800 ha, adjoining directly to Tavarnok and henceforth this property would serve as a summer residence for the young couple. Auguste was a very noble lady and entered the family well educated, intelligent and unselfish, always considering the welfare of her fellowmen. She was a perfect example of wife and mother to whom all members of the family looked up with love and reverence. As August Stummer had no male descendant and everybody was anxious that the name Stummer not become extinct, he made a petition in 1886 to adopt both his sons-in-law and to pass on to them the Hungarian barony. Albert Hardt was married with the elder daughter, Amalie, and Leopold (Poldi) Haupt with the younger one, Auguste. The petition was granted and henceforth Poldi and his descendants bore the name Haupt-Stummer.

In July 1887 I graduated with first-class honors at the first German high school in Brünn. As a reward I was promised a vacation trip and so I visited, after a short stay in Zlin, Poldi in Tökés Ujfalu and went on a trip with him to the Tátra Mountains. We climbed the Schlagendorfer peak (2000 m) and looked at all the beautiful spots of the Tátra. After a 14-day stay I traveled to Vienna, where I met my best friend, Rudi Rohrer. We then went on a trip together to Salzburg and the Tyrolian Alps. While seeing the Gross Glockner, we made the rather daring and not very reasonable decision to climb it, although we were neither prepared nor equipped for such an expedition. The first day we climbed as far as Adlersruhe (3,300 m). I was rather exhausted, so I left Poldi to do the last 500 m by himself while I waited for his return at the Adlersruhe shelter. The descent was without problems.

In the beginning of October 1887 I enrolled at the Law College of the Viennese University, and moved into a furnished room in Schottenhof. Although university way of life impressed me quite a lot, parting from my parents and home, for the first time, was rather hard. First of all, I didn’t know what to do with my great “academic” liberty. The juridical lectures, with their dry contents, had no attraction and as one could buy the professors’ written lectures at the University, I only seldom visited them. Besides, I was attending lectures about practical philosophy, with Franz Brentano, and history of arts. There was not much distraction from Viennese student life. As I didn’t have a lot of acquaintances in Vienna, I was rarely invited and would have been rather lonely had I not had Poldi and Auguste who stayed in Vienna during wintertime. Most of my nights I spent at the opera and in the theater, as the Burgtheater was at its artistic height. Life got somewhat jollier at carnival time, which I spent in Vienna as well as in Brünn. I enjoyed the balls and parties in Brünn more than in Vienna, because there I had more friends.

To get to know university life in Germany I decided to go to Heidelberg, for the summer term 1888, as I was told that it was very attractive there. At the beginning of April I started my trip that way and stayed the first three days in Munich, where I was very much impressed by the art treasures. Once I arrived in Heidelberg, I immediately looked for an apartment and soon found one in a little pension on the outskirts of the city. An elderly lady, Baroness Müller, ran it. She was a very original, fine figure from Mecklenburg, in her sixties and an exasperated enemy of Bismarck. Even with her clothes she expressed that, wearing always a “crinoline” similar to the one the Empress Eugenie wore. She had a lot of relatives among the Prussian nobles. Three of her nephews were studying in Heidelberg, Barons Axel and Jasper Maltzahn and Henning von Bülow. They often came to the pension, where I met them and we became good friends. They were active members of “Corps Vandalia” and wanted me to join, too; but as I would have to enlist for three semesters and I was allowed to study only one semester outside of Austria, I was accepted only as an official guest. I joined one students’ association, the “black association” called “Karlsruhensia,” which was recommended to me by Baroness Müller. It was called black because they didn’t wear any colored caps. They were mostly medical students, nice but rather simple people. At Baroness Müller’s pension there were lots of foreigners, mostly British and American people. At the university I registered for the law lectures, but seldom attended them. I attended assiduously the famous Kuno Fischer’s lectures, who was lecturing about modern-time philosophy. I really enjoyed these lectures, not only for their deep contents but also for their highly finished performance. I was always amazed by this man’s remarkable memory; without any notes, he could maintain his lectures for hours. My obligations with the black association were to visit two pubs and the same amount of fencing days in the fencing room every week. Besides, if some “elder man” appeared, a dinner was offered for the whole group. On Sundays we made excursions on foot; if it was far away we took the train. This way we visited the interesting towns of Worms, Speyer and Mannheim. During the Pentecostal holidays I made a trip of eight days, with a friend, so we got to know Frankfurt, Coblenz, Cologne and Bonn. My best friend in the “Karlsruhensia” was a geology student, several semesters ahead of me. He was Carl Futterer, who later on became famous through his book about his journey to China (Mongolia). Unfortunately he died very early.

Soon I felt very much at ease at the pension, well cared for by Baroness Müller. I was taking all my meals there. We were sitting at a big table for 16 persons. At the head was sitting the Baroness who, helped by her assistant, Miss Taylor, was serving the plates in a patriarchal way. Miss Taylor was a very elegant, but obviously impoverished, English lady, about 28 years old, who had taken me into her heart. She was still looking very young. Besides us an American couple, Mr. and Mrs. Weir, were staying at the pension with their son who was my age and an extremely beautiful daughter of 16, with whom I fell in love pretty soon. Her name was Julia and I often went for a walk with her and Miss Taylor, in the charming environs of Heidelberg. As Mrs. Weir couldn’t always join us, she had passed the job as a chaperon to Miss Taylor. But she missed the boat, because Miss Taylor wasn’t an effective chaperon. I don’t want to say anything bad about her because I must be grateful to her for many lovely hours. Nevertheless when Miss Julia appeared, Miss Taylor had to give way to the younger rival. We enjoyed especially the boat tours at night on the Neckar with moonlight and Chinese lantern illumination.

Several times I visited the student’s fencing ground in Hirschgasse, where the Corps and students’ association carried out and decided their duels. Finally I had to present myself there, too, because of a nightly trouble which ended in a sword, duel demand. Although I had not much practice in this sort of fencing, and my adversary was a senior-semester fencer who had fought more than 20 duels, I didn’t bother much about the affair. I got two hits on my head and my adversary one, but as my wound bled badly the fight was interrupted. It didn’t hurt very much, but I had to have a bandage on my head for several days, which was rather annoying.

Once at the Baroness’s place there was also something like a ball, in which her nephews and the younger ladies who stayed at the pension participated. Although space was rather scarce, we had great fun and I could show my skill as an organizer. This way time went by very fast and suddenly the day of my departure from Heidelberg arrived. I left this wonderful little town very unwillingly, because these four months during summer semester of 1888, without any troubles, belong to my very best memories. To bid farewell to Miss Julia was very hard for me. With the Weirs, who left the same day as I, I still made an excursion to Baden-Baden and Strassburg. A farewell gallop with Julia on the beautiful riding alley in Baden-Baden was the end of our happy times together, because I haven’t seen her since.

For the winter semester 1888-89 I registered again at the University of Vienna, where I stayed faithfully until the end of my studies. At that time I was living in Bellaria Street. At carnival time I divided my dancing skills between Vienna and Brünn. It is strange that I was never quite at ease in Vienna. The reason was perhaps my shyness, but I believe it was mainly because I couldn’t enjoy my contemporaries’ conversation and kept away from them.

In July 1889, my sister Marianne went to the health resort of Franzensbad. After she ended her medical treatment she was supposed to take a few more weeks at the seaside. She decided to go to Sassnitz on the island of Rügen and I was to accompany her there, too. I first traveled to Franzensbad and from there, with her and Miss Holweck, to Sassnitz. The rough climate of the island appealed to neither Marianne nor to me, so we traveled back home without having achieved the wanted result. During the trip I already didn’t feel well, and when we arrived back home I had to go to bed with fever. As I had no major complaints I didn’t give much importance to this flu. But as after five days there was still no change for the better, the estate’s doctor from Lukov was called. After a thorough examination he said: “You have passed a pneumonia.” My parents and I were set at ease, as the danger seemed to have passed. Unfortunately, a few days later pleurisy showed up. I had to go back to bed and felt for a few days very miserable. It was decided to end the stay in Zlin and to move back to Brünn, where our family doctor, Dr. Netolitzky, would take care of me. His opinion was that a prolonged summer would do me good and my family was advised to take me to Meran. My parents agreed to this and at the end of September the bags were packed for Meran. Completely unexpectedly a blood vessel burst while I was lifting a heavy object and few minutes later this repeated. My parents were naturally very much upset, and I was brought to bed with greatest care. I thought my last hour had come. Happily the affair was not as bad as it had appeared; nevertheless, I had to lie still on my back for several weeks. The plan to take me to Meran was canceled; I should spend the winter in an even more southern climate. We decided to go to the French Riviera, to Cannes, the place less visited by consumptives and where we knew a doctor, Dr. Veraguth. As my sister Marianne also should spend the winter in the South, it was decided that we would travel together along with her attendant, Miss Holweck. My father agreed to invite my schoolmate Gschmeidler to spend the winter with me, so I would have a good companion. He gladly accepted the invitation. Considering my weakened state, Poldi and Auguste offered to accompany and help us on our journey. So we traveled on November 19th with the Orient Express to Paris, stayed there overnight and continued next day with the Southern Express to Cannes. The sight of the sunny Riviera was for me, who never had seen a southern landscape, overwhelming. We stayed at Hotel Mont Fleury, recommended by Dr. Veraguth, and had two great rooms with alcoves on the first floor, so we could use them also as living rooms. The owner of the hotel, an honest Saxon from Leipzig, was very attentive to us. He was a passionate card player, so Gschmeidler, I, and another youngster from Vienna often played cards with him. For meals one sat at long tables and was seated by the headwaiter. We were lucky because we received very nice table-neighbors: the landowner Baron Plessen, his wife, and a five-year-old son from Schleswig Holstein. As we also were room-neighbors, we soon got into active communication and small Carili often came to play with us. We also made quite a few excursions. Further guests were two young couples from Argentina, Mr. and Madame Louro and Mr. and Madame de Souza, with whom only I maintained contact. Mr. Louro was a passionate card player and spent most of his time, better said of his nights, at Monte Carlo’s Casino. He was rather lucky in his game and once won 600.00 Frs., but at the same time he neglected his wife. You can’t blame her if she tried to take comfort elsewhere. I surely didn’t blame her for it. We had poker parties, but played for a very low stake, with the Souza couple and Mrs. Louro. One night Mr. Louro appeared and wanted to join us, but as the stakes were too low for him, he immediately risked 1000 Frs. which frightened the others. I sensed the bluff and held the stake; it turned out that my card was higher and I would have won the game, but both ladies protested that the stake was too high. So I delivered the 1000 Frs. bill, after which Louro tore it into pieces. Besides that, there were no disagreeable incidents. The most remarkable appearances in Hotel Mont Fleury were two Russian ladies, Princess Schahovskoy and Countess Woronzoff, who were striking not only by their beauty but also by their flashy jewelry. The Woronzoff woman had a little Mongolian touch, which granted her beauty certain piquancy. The rest of the guests were mainly from Britain and not very interesting.

The weather in December was often rainy, but with the beginning of January we had splendid weather, which often helped us to realize nice excursions. We went to see Marseille, where we stayed for a few days. At carnival time there was a ball in the hotel and I was appointed leading dancer. Besides that we went to see the carnival of Nice, and participated in a battle of “confetti” which was great fun. We were in Monte Carlo only twice. Gschmeidler and I played with little success, but Marianne had the rare luck to win twice “plein” (full) on one afternoon. She played the number 23, which was her age.

In March we received a visit from Uncle Schoeller and Cousin Heda, who on their way home from Paris stopped for a few days at the Riviera. Our stay in Cannes also came slowly to its end. The stay had done us both, Marianne and me, much good and Dr. Veraguth could dismiss me from his care as completely recovered. We left Cannes the 13th of April, but this time we took our journey through Italy and stayed a few days in Genoa and Milan. Finally we arrived in Brünn the 23rd of April and were received by our parents who had missed us throughout the whole winter they had stayed alone.

Soon afterwards I received an invitation to Uncle Gustav Schoeller’s sixtieth birthday celebration. Among the invited guests was Baron August Phull with his wife and daughter Hedwig, a young girl of 16, who on this day made her first step into big society. The happiness she felt about this filled her eyes and whole face with such a radiant look that my heart stood still for a moment when I saw her. This first impression stayed forever, and five years later this girl was my wife.

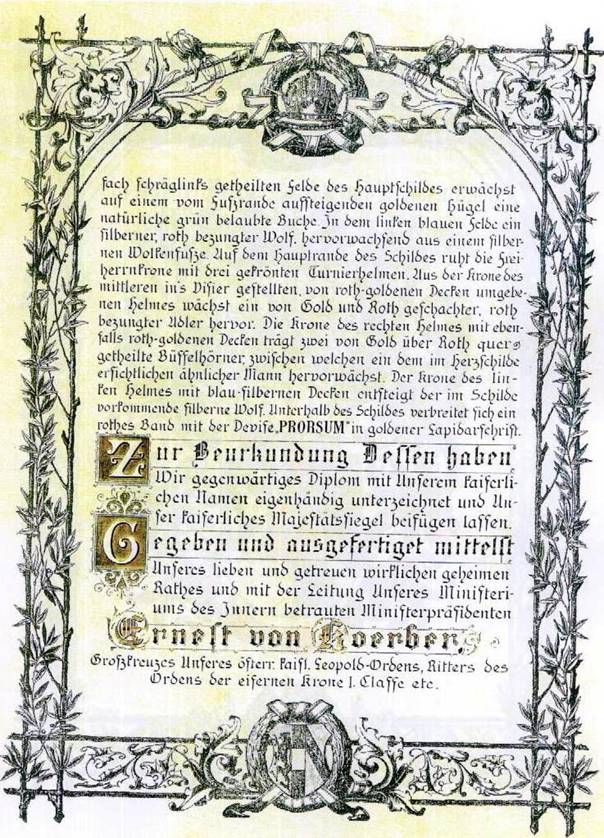

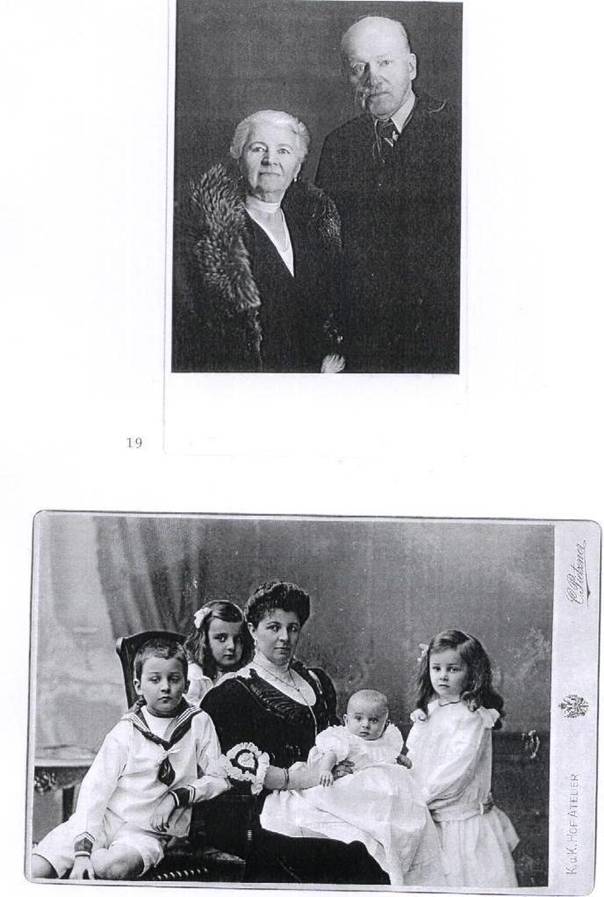

Meanwhile, my brother Poldi’s family fortunately increased. In their Viennese winter-apartment, Teinfal Street 1, the following children were born: Gertrud, 10, 27, 1886; Leo, 10, 14, 1887; August, 01, 22, 1889. The successively close births of her children had affected Auguste’s health and she was prescribed a cold water cure, which she took in August 1890, in the Suisse spa of Rigikaltbad. As I had finished my studies at the University of Vienna, and was free, I also traveled to Rigikaltbad to visit Auguste and Poldi. I loved the place and stayed for 14 days until Auguste finished her treatment. We then took a coach tour (no car existed at that time), starting in St. Gotthard, going first to the Como Lake, then over the Rhone Glacier to the Lake of Geneva. Poldi and Auguste turned back home from there, while I still made a side trip to the Rhine-falls in Schaffhausen.

In Rigi I made the acquaintance of a young Turkish diplomat called Osman Bey. He told me a lot of interesting details about the situation in Turkey. Later on, he was an important person during the young-Turkish revolution in 1908, but he seemed to have perished with it because I never again heard from him.

In October 1890, I went back to Vienna to the university and took first-class honors with my first public law exam.

Christmas Eve I spent with my parents in Brünn, where I also stayed for the forthcoming carnival. Social life in Brünn was a very active one. Besides the four nobles’ picnics, there were great official balls at the governor and major’s places and two officers’ balls. Besides that, seven or eight house balls (at the Haupts’, Phulls’, and Offermanns’, Teubers’, Brands‘ and Reibhorns’ places.) I danced the “cotillion” with Hedwig Phull at the first picnic, immediately at the beginning of carnival. We had a very good time and excellent conversation and as I arrived at home early morning, I was convinced I had found my future life’s companion. The next balls, where I had opportunity to dedicate myself to Hedwig, brought me the conviction that she had the same feelings that I had. With this certainty in our hearts we spent a wonderful and happy time through this winter and spring.

In November 1891, Hedwig’s grandmother, Mrs. Jacobine Staehlin, died in Brünn, unacceptably quickly by a stroke of apoplexy at the age of 74. This death destroyed our hopes for frequent get-togethers in the following winter season, because Hedwig naturally couldn’t take part in carnival events and at that time there was no winter sport; so we met only frequently at the skating court. So carnival 1892 passed without attraction. No matter with whom I was dancing Hedwig’s image accompanied me and I found no interest in the young ladies of Brünn’s society. I immersed myself into my studies and managed from January 1 until July 31st, 1892, to pass three exams of law, two of them with honors, and got hold of my doctor’s title.

Poldi and Auguste decided to spend the winter with their children in the south and rented for this reason a villa in Meran from their property neighbors Weiss. They also invited Marianne and me to join them. I happily accepted this invitation and left, in the beginning of March, for four weeks with them. Meran at that time was the meeting point for nobles from the Alp countries and was cramped with good-looking countesses but only very few young men to match them. Therefore, I was very cordially received and passed an extremely amusing time. In springtime Poldi went back to Tökés with his family as Auguste was again awaiting a baby. The grandparents Haupt (and I as a substitute of grandfather Leopold) were the chosen godparents. So my mother and I left for Tökés at the end of May, where on May 31st, 1892, a girl, named Carola, was born.

Once back in Brünn I asked for admission to the political composition department of the government and my request was granted. On August 15th, 1892, I received my attachment to the department 1 (culture), whose boss was Baron Bamberg. He was a very intelligent and educated person but extremely malicious and let his subordinates feel it. Physically he was a caricature; two meters long, deaf and very shortsighted. He liked to tease me that I was dispatching too few documents, until one day I lost my patience and replied to him: “Yes, so many documents a boss can sign but a subordinate can’t supply.” My companion in the room, Dr. Gerstner, burst into loud laughter, but my friendly terms with Bamberg weren’t interrupted. Poor man, a few years later, he became blind and committed suicide.

The Phulls passed the summer months in Adamstal, near Brünn, where they rented a small villa from Dr. Klob. My parents were staying in Zlin while I, even in summer, was bound to Brünn, with my work at the government. As a diversion I went on Sundays to Phulls, where usually a lot of youth were gathering. As I had horses at my disposal I could make the 15 km through the beautiful woods with a coach; this trip was especially romantic at night.

In November 1892, my schooldays friend Rudi Rohrer, in spite of the opposition of his future mother-in-law, married his longtime beloved Margarete (Gretl) Krackhardt. Hedwig, who was a great friend of Gretl, was naturally at the wedding party, as was I.

Carnival ’93 started very promising. Governor Loebl had brought to Brünn a bunch of young Polish composition probationers and they were a welcomed increase to the dancing-men material. They were, among others: Count Michalowski, Count Lassowski, Baron Hajdl, and Taddeus Loebl, son of the governor. In the following Lent, one was playing theater at the Haupts in the Kröna. The big hall in the garden section was just perfect for this purpose. April ’93 Clara Reibhorn married Count Eugen Braida, Lieutenant in the 6th Dragoon Regiment. The bishop celebrated the wedding in the cathedral of Brünn with great pomp. The bridesmaids were looking very sweet in their pink dresses; Hedwig was among them.

At the beginning of August I started my first four-weeks vacation. First I went to Heidelberg to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Karlsruhensia. There I met my old friend Futterer, who invited me to go on a tour through the Ziller Valley Alps, where he wanted to make his geologic analysis. This just suited me, as I knew that the Phulls were staying for the summer in Landro, whereto my hiking would take me without any problems. We started middle of August and drove first to Mayerhofen, stayed there overnight, started next day early morning to reach the shelter of the Pfitscher Ridge, 2000 m high. Futterer got sick there and I had to leave him and continue my wandering to Landro alone. I arrived, just before dinner, after 13 hours of walk. The Phulls weren’t yet in the dining room, because they had come back late from a picnic. The chief waiter appointed me a place next to theirs. Mother Therese was quite astonished as, on entering, she caught sight of me as a neighbor. Hedwig was very happy and showed this without any fear. I stayed for a few days in Landro, as long as the Phulls were there, and left together with them. The rest of my leave I spent in Zlin and afterwards started my work at the government office again.

November 1893, I passed my practical political exam with first-class honors. At the same time I was transferred from department 1 to department 3 (municipality and citizenship affairs) under municipal alderman Nasowsky. Work here was much more interesting and stimulating than in department 1 and I devoted myself with so much eagerness that I became known as an expert for citizenship affairs. Oktav Bleyleben, who was a member of the presidency, told me later that the governor Baron Spens-Boden, who meanwhile had been nominated instead of Loebl, told him that I was his best composition probationer. This good opinion helped me a lot later when I reentered Moravia Governor’s Office.

In the year 1894 there were no big changes in my life. Now, as before, my heart was engaged and Hedwig and I were only waiting for my call to the Foreign Office to declare myself definitively. This occurred in December 1894, and I started my work in Vienna on January 1st, 1895. I wanted to participate at the carnival of Vienna to make sure that my conviction and decision to marry Hedwig was steady and confirmed. I plunged into the so-called second society (military, high civil servants and also finances). Mostly I mixed with the families of Gablenz, Oldofredi, Konradsheim and Pasetti. Among the gentlemen of the society there was a young man, Baron Forstner, with whom I made friends, but unfortunately he died very soon. In summertime Forstner and I used to go to the Gablenz to Neu-Waldegg, where a lot of youth met on Sundays. I also was quite busy with my studies for the diplomatist exam, which was to occur in November ’95.

In August I traveled to the summer resort Weissenbach on Lake Attersee, where the Phulls were staying at a summer resort. In the beginning of September Cari and I went for a fortnight to Tökes, where we spent very delightful days. At Countess Matuschka’s, an estate neighbor, there were three jolly ladies, the castle owner’s visiting nieces, whom we often went to see. They were: Baroness Malenitza, called Pitzi; Gabriele Rodakowska, a cousin of Mimi Rodakowska Lamezan; and Angele von Haut-Charmony. We did a lot of horseback riding, hunting, and once we danced in our host’s castle in Tavarnok. After this lovely stay I went back to Vienna. I was staying with Poldi and Auguste, who at that time were moving to Budapest. I stayed for another couple of weeks in this empty apartment and registered, middle of November, for the diplomatic exam. We were only three candidates: Prince Carl Schwarzenberg, Count Herbert Herberstein, and I. I succeeded in the exam with honors, Schwarzenberg with good result, and Herberstein, who didn’t know anything, was rejected and as a consolation he was appointed military attaché in Paris.

The hard studies had affected my nerves, so I asked for six weeks of holidays that I spent in Meran, where Marianne was staying for medical treatment. There I met a lot of acquaintances and also learned to know many new people. Among them were the Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Berlin, Count Széchényi and his juvenile son László, who followed me closely, because we were both flirting with a good-looking English girl. He later married a Miss Vanderbilt and became the Hungarian ambassador in Washington.

I got a nomination as first secretary to the Legation in Tokyo, and had to go to thank His Majesty for it. For this reason I was ordered to an audience. It was the first time that I got to see Emperor Francis Josef. Immediately after that I got my attachment to the Austrian-Hungarian Legation in Tokyo, which I wasn’t happy about. When I got back to Brünn I told my parents I had accepted the job for Japan. The thought of so long a separation alarmed them very much. At the same time I also told them I wanted to marry Hedwig Phull before I left, since she and I had been as one for quite a while. I asked my father to call on Baron Phull and to announce me for one of the next days. As for myself, I had to leave once more for Vienna, so I could appear before the parents Phull to propose officially on the evening of January 20th, 1896. I got their consent, but at the same time they let me know that the thought of their daughter leaving for Japan troubled them a lot. But as Hedwig said she would go with me till the end of the world, all my doubts vanished.

Baron August von Phull originated from a very ancient noble family from northern Germany whose genealogical tree can be proved way back to the 13th century. Through the centuries one branch of the family moved south to Würtenberg, while the other part stayed on the ancestral seat in Jahnsfeld next to Berlin. Baron August von Phull derives from the Würtenberg line. His wife Therese, born Staehlin, comes from a patrician family from Lindau (Bavaria) who emigrated to Brünn. Hedwig was born November 20th, 1873, and had two brothers, August (Gustl), born March 24th, 1870, and Walter, born March 11th, 1876.

After having waited for several years, we now were officially engaged. To celebrate this event our true friends, the Rohrers, Aunt Auguste and Sofie, as well as Cousin Fritz Schoeller, gathered at the Phull’s house. All preparations for the wedding had to be rushed, because the ship we wanted to travel with, “Sachsen”(Saxon) 6000 t, from the North-German Lloyd, was leaving Naples on March 11th. The wedding day was fixed for March 2nd. Mother Phull and Hedwig had their hands full of work preparing the trousseau and shipping it to Japan, while I was in Vienna fixing all the details and formalities of our journey. Even before our departure about six big tin-plated chests, with silver, glass, china and linen, were shipped to Tokyo on an Austrian freight-steamer. I was travelling up and down between Vienna and Brünn till the wedding day on March the 2nd arrived. I got the permission of Brünn’s bishop, Dr. Bauer, to have our wedding celebrated in the Episcopalian chapel of the cathedral by St. Magdalene’s vicar, Jakob Bartos. After the ceremony at the cathedral we had, in the apartment of Aunt Auguste Schoeller, an evangelical blessing by Dr. Trautenberger. Our wedding witnesses were, for me Uncle Raul Krieghammer, and for Hedwig, Uncle Gustav Schoeller. After the church ceremonies, all the guests gathered at the Phull’s apartment, where the lunch was served. At 3:30 p.m. the moment arrived when we had to say goodbye to parents, brothers and sisters. Due to the circumstances, it was understandable that this was a very hard moment. We left by train to Vienna where we stayed at the Hotel Bristol. Next day, we received a charming visit from the grandparents Stummer, who wished to see us once more. We took the sleeping car, at night, to Venice, where we stayed at the Grand Hotel. There my cousin Edi Friedenfelds, a navy lieutenant stationed in Pola, visited us. I questioned him a lot about the circumstances in Japan and China. He had recently spent two years on an Austrian cruiser in East Asia. He stayed mainly on the Jangsekiang River and from there they went to different places in China. His descriptions weren’t very encouraging. No railways were existing in China. Travelling had to be done on the great rivers or by horseback. The night stops were in very miserable places. Summarizing, he explained to me, only very healthy people with excellent nerves could stand the burdens of such a kind of journey. But these were the qualities I least possessed. My decision to dare this journey was badly shaken. After a walk on the Marcus Square, cousin Edi left that very evening, back to Pola.

Next day we left for Rome, where we stayed at the Grand Hotel; and as it was overbooked we got the Prince’s room for the normal price. There awaited us my old driver Emil, an honest Saxon, now our chamberlain, and our maidservant Marie, an elderly, well-traveled, but not very pleasant person. They were supposed to accompany us on our way to Japan. In Rome we stayed only two days and looked at the most famous objects of interest. I also paid my respects to the Austro-Hungarian ambassador and my colleague, Baron Flottow, recently nominated an attaché. I was envying him this position, which I rather would have had. On March 9th we traveled to Napoli, where we stayed for only one night and then boarded the Lloyd’s steamer “Sachsen” that had just arrived. There we had our first disappointment. Due to overbooking, my reservation for a first-class double-bed cabin to Japan couldn’t be accommodated and we got a small cabin next to the engine room. The heat was unbearable, besides having cockroaches, which weren’t helpful in making our stay more agreeable. I of course created a rumpus, but could get a promise for a better cabin only after Bombay. So we went to bed very concerned about it. As I couldn’t sleep, I went before sunrise to the upper deck to scrutinize once more my decision to start this journey. A messenger came up at that time with a telegram from the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Office asking me to wait for the Ambassador, Count Wydenbruck, in Shanghai and to accompany him to Peking. This meant I would have to leave Hedwig in Shanghai under our counsel general Mr. and Mrs. Haas’s guard. I also wasn’t equipped for such an expedition that would occur mainly on horseback. This telegram brought the decision. The thought of being separated from Hedwig in a foreign country for a long time seemed to me unbearable. I also wasn’t disposed for the harassment of such a ride. I conferred about this new situation with Hedwig and our decision to cancel the journey was very quickly made. Our innumerable luggage had to be unloaded in haste and taken to the island under the control of Emil and Marie, who were very disappointed to leave the boat just when the military band was playing for the farewell of the boat. I sent a telegram to Aulic Councilor von Mittag that I was not able to travel because of sickness and that I was ready to take the consequences and to quit the diplomatic service. We wrote letters of similar content to our parents, but telling them we were in good health and intended to make a longer honeymoon. With a relieved feeling I saw the “Sachsen” in the distance disappear. Only then we started our beautiful honeymoon. Italy’s journeys were so often described that I will not repeat all that was said before or make a Bädeker’s “Italy” (German travel guide) excerpt. I am content to enumerate the places we visited. First we stayed a few days in Naples, especially to be able to see Pompeii. From there we sent Emil and Marie, with the unnecessary luggage, back home to wait for us there. In Rome we stayed about six days and stopped at a smaller hotel, because I wanted to avoid a meeting with my colleagues from the Embassy. Our next stop was Florence where we stayed four days. Meanwhile it turned springlike and we went, passing Milan, to Palanza at the lake of Maggiore, where we spent the Easter holidays and set out for Bellagio at Lake Como. Once we made an excursion with two oarsmen rowing boat and got into a bad storm, which left our trip rather unpleasant but we eventually got out of it safe and sound. From Bellagio we went back for three days to Milan, then to Verona where the tremendous Scaliger’s gothic tombs impressed us more than Julia’s supposed home. From Verona we left for Venice where this time we stayed longer. Our next aim was Triest. There we inquired, at the Austrian Lloyd, the whereabouts of our big luggage that was shipped directly to Japan. We were told that it was unloaded in good shape in Kobe, the nearest harbor to Europe, and was awaiting shipping orders. I immediately ordered it back to Triest. At the Lloyd’s agency in Kobe they, by mistake, shipped back another diplomat’s luggage instead of ours. It took several months to get this mistake straightened out, but finally we received in a miraculous way our luggage undamaged. From Trieste we made a few days’ trip to Abbazia and then started, mid-May, our way back to Zlin. My parents, with Marianne as well as the Phulls, were waiting for us there. Unfortunately our return wasn’t unclouded because we found my mother in a very bad mood. The melancholic depression she had after our departure was still continuing, and it wasn’t before another few years that she more or less reached her balance again. After the wonderful weeks of honeymoon this contrast of depressive mood at home was painful. On top of this, a few days after our arrival, I also got sick with fever. As the doctors couldn’t explain the reason, they were supposing I could have gotten a malaria infection in Napoli; they suggested for the benefit of the nerves to take a cold water cure in Reichenhall. This proposition suited us very well and so we left already mid-June with Marianne and Miss Holweck to the salt city. We met different friends there: the Couple Count Dessewffy, and a young Baron Bruxelles, with whom we had a steady tennis party. Walter Phull joined us, too, when he came to visit us. The cold water cure did me a lot of good and just a few days later I felt excellent. After a three-week stay at the spa we got back to Zlin. We visited from here Aunt Jenny Pokorny, my mother’s sister, in Pressburg (Bratislava), where her husband was seated with his division. I also took Hedwig to Tökés to Poldi’s where she was very well received and liked to stay. We met there Aunt Thesy Henneberg and Nanine. Aunt Thesy died a few months later in Gilli.

The worries about my future followed now, because it seemed dubious that after my withdrawal from the Foreign Office I would be readmitted to Moravia’s Government Service. The governor still was Baron Spens, who formerly had praised me a lot; this happened to be useful now. When I personally went to see him and asked for my readmission to the Government Service, he greeted me very heartily and immediately gave his approval to my request. I asked for a job at the district office of Göding, which I preferred because it was very near to Zlin. Baron Spens also approved this wish of mine. From Brünn I went to Gödig to present my homage to the district manager, Baron August Fries, whom I also knew from former times; he also greeted me very cordially. The next days I spent looking for an apartment. Finally I succeeded in finding an empty schoolhouse with four rooms, which were divided by a large porch into two pairs of two rooms each, plus side-rooms.

As I wanted to have horses and a carriage I also had to find a place for them. Now we drove with my mother-in-law Therese for several days to Vienna to order the furniture. From the stock of Archduke Otto (von Hapsburg) I bought a pair of wonderful half-blood horses, and although they were over 12 years old they served me well for another ten years. One of the mares, Ariosa, brought me four beautiful foals. A few weeks later I bought a riding horse from Roderich O’Donnell, 2nd Lieutenant in the 6th Dragoon Regiment. The setting up of our apartment, with which our cousin Fritz Schoeller, (at that time a 6th Dragoon lieutenant there), was very helpful, progressed quickly and so we were able to move to it in the beginning of August, 1896. I was able to start my job at the district management of Göding on September 1st. On September 17th, 1896, Hedwig’s grandfather, Gustav Adolf Staehlin (1816-1905), was celebrating his 80th birthday. For this occasion there was a big family and friends get-together at the Phull parents’ apartment.

Once back in Göding I dedicated myself with great eagerness to my job. The district management’s personnel consisted of, besides the manager Baron Fries, an older district clerk named Hlosek, and the composition (law clerk) Baron Sterneck, who soon was transferred to Ungarisch Hradisch. I then had to take over his jobs. Baron Fries was a very nice boss but lacking in energy; however, his much younger wife, born Marie-Luise von Tersch, possessed enough of it. She was like her mother a very much in need of love and gay person, who was most popular with the dragoon officers stationed in Göding. Hedwig, although of the same age, didn’t get along with her. Among the 6th Dragoon 4th squadron stationed in Göding there were two younger couples, Baron Weber and von Rodakowski, who were our best friends. Hedwig’s best friend was Mimi Rodakowska, born Countess Lamezan. Carl von Dittel and his wife Elsa, born Mautner Markhof, also were among our acquaintances. They had a small property (Josefsdorf) just next to Göding. In our cozy little apartment we felt very much at ease, although during my office hours Hedwig was sometimes lonely. Mama Therese came visiting from time to time, as well as other friends from Vienna and Brünn. The warmer months’ evening hours we spent by driving out with the horse coach to the beautiful valley woods full of deer and large game. The only annoyance was the great number of gnats. The excellent terrain for horseback riding in the Emperor’s property let me have lovely gallops in the morning hours, when I often was joined by Helen Weber and Mimi Rodakowska.

Christmas we spent in Brünn with the Phulls in a big family circle.

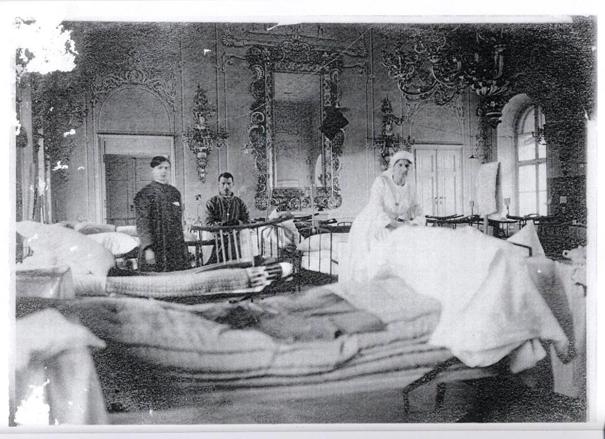

In winter 1897 Baroness Fries, as president of the Red Cross, was organizing a benefit theater and I also had to act a part. Unfortunately Hedwig couldn’t take part, as she already was expecting. Mama Therese came already at the end of April with the midwife Lady Zopp. On May 21st, Professor (medical doctor) Riedinger arrived from Brünn and on the 22nd, at six in the morning our first child, a beautiful, well-shaped boy, was born. Happiness was great and for the first time in my life I embraced and kissed my mother-in-law. At that very moment a squadron headed by Fritz Schoeller rode by our window and I could immediately tell him the good news. The first visitor next day was Papa Phull, the happy grandfather, who came from Brünn. The baptism was four weeks later in Göding’s church and the child was named Stefan Leopold August. The godparents were Grandfather Leopold and Grandmother Therese. But as Grandfather Leopold had a hemorrhage in his eye and couldn’t come, Rudi Rohrer represented him. The baptism dinner guests were the parents Phull, Gustl, Mama Anna, Marianne, Miss Holweck, the Rohrer couple and Mrs. Zopp. Mrs. Zopp stayed for four weeks and in this time Hedwig recovered fast and the baby was doing fine.

As there was not much space in our apartment, we looked for a larger one. Luckily, the mill owner Gmeiner, who was living in a nice one-story house, had to rent the lower floor of six rooms and offered it to us. We were happy to take it, and after cleaning and de-bugging the apartment we already could move to it on July 1st. End of July I took my vacation and spent it with Steffi in Zlin. At that time I also got my nomination as district law clerk. In August the 6th Dragoon Regiment was transferred to Enns and Wels. Instead of them the 15th Dragoon Regiment moved to Göding’s barracks. Among the married officers there were three very compatible couples with whom we made friends very soon. The officers were Captain Baron Skrbenski, Count Merveld and Prince August Lobkowitz. At the same time the state-owned stallion depot was transferred to a newly built barrack in Göding. The depot’s commander-in-chief was Baron Felix Bianchi, who also was a good and eager tennis player. As tennis was played also by the 15th Dragoons we often had good tennis parties in summer.